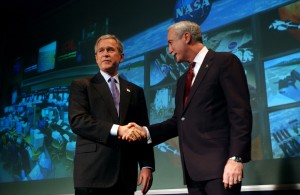

President George W. Bush and NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe on January 14, 2004, the day the Vision for Space Exploration was announced.

Near the end of my recent two hour co-appearance with Dr. Jim Vedda on The Space Show (October 19, 2012), an ongoing misconception emerged about the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) and prompts me to detail some of the history of the VSE and its original intent. Such a review is timely as discussions rage about NASA’s current and future direction.

Look up the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) on Wikipedia. You will read that it was a “visionary plan for space” announced by President George W. Bush in January 2004. The VSE was devised to give our national civil space program a long-range direction – making human missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond the new strategic horizon for NASA, our national space agency. With the bipartisan passage of the NASA Authorization Act of 2005, the VSE became our national space policy; the same policy was renewed three years later by Congress. Then, in the spring of 2010, it was terminated by the current administration.

Where did the VSE come from, what exactly happened to it and why did it go away? Answering these questions requires some background in order to give the context of the decisions about the VSE, and to explain how it came to be implemented by NASA.

After the Apollo program ended, the spaceflight community wanted ambitious, long-term goals for NASA, including human voyages into deep space, assuring strong U.S. leadership in space exploration, technology and science. The agency itself has long subscribed to the paradigm first outlined by Wernher von Braun in the late 1940s. It called for an Earth-to-low Earth orbit (LEO) rocket (preferably reusable), an Earth-orbiting space station, a Moon tug (for missions beyond LEO into cislunar space), and a manned Mars vehicle. This sequence made logical sense (in that each step enabled the next step) and as technology improved and matured, humanity would become a space faring species.

The geopolitical realities of the Cold War (Sputnik) intruded on this logical sequence, initiating America’s bold challenge to the Soviets, followed by a headlong drive to land a man on the Moon first. Once we had won the Moon race, there was no political need to continue the Apollo lunar missions and spaceflight once again was relegated to the background of modern American life. NASA returned to the von Braun architecture as best it could and implemented the first two steps – the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station (ISS), programs whose principal operating arena was low Earth orbit.

However, we already had “jumped ahead” in the von Braun sequence and been beyond LEO – we had walked and worked on the Moon. Many working in space activities looked back on that program as a lost “Golden Age,” very much in the sense that citizens of the latter-day Roman Empire looked upon the Age of Augustus. Throughout the eighties and nineties, many different proposals and initiatives attempted to define a new strategic goal for NASA, most often by attempting to resurrect the use of either the Moon or Mars part of the von Braun architecture as its centerpiece. In fact, these strategy initiatives frequently became Moon OR Mars campaigns, with each camp proclaiming their superior qualities and/or advantages.

In the wake of the 1986 loss of Space Shuttle Challenger (and on the twentieth anniversary of Apollo 11’s first landing on the Moon in 1989), President George H. W. Bush announced what was dubbed the Space Exploration Initiative (SEI). SEI addressed the space goals sought by both Moon and Mars advocates. The space agency quickly studied the concept and announced it was achievable on a timescale of about thirty years and would cost around $500 billion (1990 dollars). Many gasped at that headline-grabbing cost estimate and detailed program facts were never as “good” as the headline – that this was the total aggregate cost to the agency for a thirty year time period and corresponded to roughly a doubling of the then-current NASA budget (at that time, about $10 billion per year or roughly 1% of our national budget).

Considering the scale and scope of what was being proposed, this number was not unreasonable. To give some context, during the time period between 1980 and 1995, the annual budget of the Department of Energy (DoE) ramped up from $8.4 billion to $18.4 billion (after the threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union had already receded). Over the course of the past thirty years, DoE’s annual budget would exceed NASA’s by almost 50%. Money spent on entitlements (e.g., Medicare, student loans) and social welfare programs accelerated and increased at much higher rates.

The “$500 billion” SEI program was deemed too expensive and in the early 1990s, it was quietly abandoned. Assembly of the ISS kept NASA busy during the following six years and in 2000, the orbiting space station became operational. Then in early 2003, the Space Shuttle Columbia and all seven members of the crew were tragically lost when the vehicle broke apart during re-entry. Once again, the agency looked to the White House for strategic guidance.

The Columbia accident initiated a top-level (nearly year-long) review of the goals and strategies of the U.S. civil space program. Much of this work is chronicled in New Moon Rising: The Making of America’s New Space Vision and the Remaking of NASA(Frank Sietzen and Keith Cowing, 2004), which describes the “sausage-making” phase of space policy in the Bush White House. Although that story is well told there, I will add a few new details not covered in their book.

I first became aware of this activity in mid-2003. I had been making the rounds in various venues, preaching the gospel of lunar return to anyone willing to listen. I received a favorable reaction from many people, including many at NASA (one was Gen. Jefferson Davis “Beak” Howell, the Director of the Johnson Space Center in Houston) and retired space veterans (such as Tom Rogers, one of the key people involved in developing the Atlas launch vehicle and many other early space projects). Another key player was Dr. Klaus Heiss, an economist who originally made the case for developing the Space Shuttle and who had worked with President Reagan on the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). A friend of George Bush the elder, Klaus had a private meeting with President Bush in the spring of 2003, where he urged him to focus on building a lunar base. Klaus and several others (including most notably Presidential Science Advisor John Marburger and his staff) understood the importance and value of learning how to use the resources of the Moon to create a permanent, sustainable space faring infrastructure. This idea was central, not peripheral, to the emergence of lunar return as a major theme of the new direction being formulated by the White House-NASA study group. The intent of the VSE was to put forth a strategic direction for the next few decades (leading to long-term space utility), so an ambitious, capability-creating paradigm was sought (and why President Bush specifically mentioned the use of lunar resources in his 2004 space policy speech).

However, the mission of the VSE became muddled and Mars advocacy was the reason. Although President Bush clearly understood the purpose and value of learning how to create new capability by going to the Moon, he wanted to demonstrate its wider relevance by including Mars as a goal in (not the goal of) the new VSE. This episode, memorably recorded in the Sietzen and Cowing book, occurred during the meeting to make a final decision on the VSE, when the President asked, “This is more than just the Moon, isn’t it?” – that the VSE was about creating the capability to do anything and everything in space, with the Moon as the enabling asset and lunar return the key to making use of that rich commodity.

Of the roughly 2000 words that make up the VSE speech President Bush delivered on January 14, 2004, the Moon is mentioned eleven (11) times. Moreover, the specific activities to be undertaken on the Moon are set forth and described, including learning how to live and work there for increasing periods of time and using its material and energy resources. Mars is mentioned four (4) times and no specific activities to be undertaken there are described. But “Mars” was the only word that many in NASA and elsewhere in the space community heard or wanted to hear. Almost immediately, the intent of the VSE to go to the Moon and learn to use what it had to offer was forgotten or ignored, at least by many below the Associate Administrator level (and a few at and above that level). In consequence, the new initiative found itself off course rather quickly. I will describe those events in my next post.

I think there has always been an obsession with Mars because Mars is viewed as the best place in the solar system, beyond the Earth, for humans to colonize. Of course, NASA is not in the colonization business, its in the pioneering business (when allowed to do so!).

Ironically, Mars first advocates don’t want NASA to pioneer the Moon or Mars by setting up permanent outpost which would probably lead to colonization by private industry. They simply want NASA to do an Apollo style visit to the red planet and then, I guess, go on to do something else!

Real Mars advocates should want NASA to go to Mars, not simply as a one time stunt for an elite few– but to stay! This would allow NASA to thoroughly explore Mars with both humans and robots together on the Martian surface.

A lunar outpost program would make it a lot cheaper and easier to get to Mars if we utilize lunar water resources for fuel, air, drinking, washing, and mass shielding. And the same basic architecture used for a lunar outpost could also be used for permanent outpost on the surface of Mars. This would dramatically reduce the development cost for going and staying on Mars.

IMO, the Apollo program really should have been a lunar outpost program right from the start! Sure we needed to find out if astronauts could actually get to the Moon and return safely to the Earth a few times. But afterwards (maybe after Apollo 15), preparations should have been made to use the Apollo/Saturn architecture for a space station (Skylab) and a lunar base (using unmanned LM technology to place habitat modules on the lunar surface). Such a lunar outpost program would have captured the imagination of the American people since it would have been viewed as a progressive program that could have eventually led to lunar colonization by private industry.

This probably would have happened if the Soviet Union had eventually followed America to the lunar surface in the 1970s. There was no way our politicians and our military would have allowed the communist to permanently occupy the surface of the Moon without a permanent American presence there:-)

Unfortunately, once the Soviets lost interest in going to the Moon, so did America’s politicians! And our manned space program and even our general economy has been in decline ever since! America’s enormous investment in space development during the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo era catalyzed some of the highest economic growth the US has ever seen!

Marcel F. Williams

Pingback: Mission: Tomorrow » The Vision for Space Exploration: A Brief History (Part 1) | Spudis Lunar Resources

Paul

An excellent synopsis of the pre and early VSE. As one of the participants in the early VSE era with NASA in their post Bush announcement I saw a lot of the creative tensions from the inside. At first everything was very positive and for example, at a four day confab at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Pasadena the Bush VSE speech was waved around like the bible that we had to adhere to in developing the plans. However, even then a curious dichotomy was developing that helped to plant the seeds of the eventual running off the rails of the whole process.

The first fight that should have never happened was the fight between the idea of lunar Sorties and a lunar outpost. Our friend Harrison Schmidt was adamant about sorties as the best way to fully explore the Moon and eventually find an outpost. However, this was exceedingly expensive and was used by the lunar/mars “touch and go” crowd as a means to eliminate any long term activities on the Moon, which they derided as “ISS on the Moon”.

The second and most mystifying was the fight over ISRU or In Situ Resource Utilization. Even though George Bush specifically mentioned using the resources of the Moon, propellants and even spacecraft assembled there as the basis for going to Mars, that part was almost immediately derided buy the Mars crowd and only lukewarmly supported by the lunar supporters.

I am always tempted to be astonished at our community and its cultural blindness to ISRU but it can be explained by a narrow perspective of the aerospace engineering community. Early on in the VSE era ISRU was excluded from the baseline because of its “low TRL” or technology readiness level.

That statement was true, but only in the most narrow Aerospace industry level. If you look at any literature search on ISRU on NTRS or other internet sources, most of the work, the serious development work, still dates to the 1990’s. There have been amazing advances in materials processing since that era that simply have not been integrated into the thinking of the aerospace architecture systems engineers that develop these plans for the Moon and or Mars.

All of this was mooted with the departure of Sean O’Keefe and the arrival of Dr. Griffin who abandoned all fiscal reason and adopted his Apollo on steroids approach to exploration.

The low-TRL issue arises naturally from a human-focused program (at one point there was something called the Human Space Flight (HSF) program or directorate). When one focuses on sending humans to the Moon, then a natural conservatism will creep in, because no one would wish to have an accident involved dead astronauts on the Moon. When sending humans to the Moon is the goal, then precursor robotic missions seem like bumps in the road, something to get past quickly.

However, if development of cis-lunar space is the goal and precursor robotic missions are enthusiastically supported, then missions for which the very purpose is to raise TRL levels become consistent with that goal.

Focusing on sending humans to the Moon is poison.

Fascinating stuff. No wonder the original Vision said nothing about “monster rockets”.

When Craig Steidle started at AA for ESMD the folks from MSFC trundled up to HQ to tell him how desperately a HLV was needed to go to the Moon and Mars. Steidle and O’Keefe looked at the budget and said we don’t have the money for this and this led to both the CE&R and the H&RT studies that were well under way or nearly completed but killed by the Griffin led NASA in favor of the Ares vehicle.

Challenger tragedy was in 1986, not 1987.

Yes, of course. Thank you for the correction.

Excellent piece!

I would bring up an aspect that may be too subtle a difference to matter, or be the key to why we are where we are. You write:

” Once we had won the Moon race, there was no political need to continue the Apollo lunar missions and spaceflight once again was relegated to the background of modern American life. NASA returned to the von Braun architecture as best it could and implemented the first two steps – the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station (ISS).”

My experience at the time was of an agency trying to stay relevant at all costs and that meant supporting spaceflight for direct, tangible human benefit. The shuttle was the cheap launcher that was reliable by dint of having humans fly it. The space station was something to do with the already built shuttle infrastructure when the shuttle was revealed to not be a space truck – rather than the next rational step of a von Braun architecture.

Why programs like SEI and VSE (and what Von Braun proposed) never go anyplace because maybe for reasons as “Rocketpunk” (days of future past), http://www.projectrho.com/rocket/macguffinite.php which mentions, “The sad fact of the matter is that it is about a thousand times cheaper to colonize Antarctica than it is to colonize Mars. [snip] Yet there is no Antarctican land-rush. One would suspect that there is no Martian land-rush either, except among a few who find the concept to be romantic [because it is so far away and difficult to do.]

The sad fact of the matter is that it is about a thousand times cheaper to colonize Antarctica than it is to colonize Mars. [snip] Yet there is no Antarctican land-rush

This is a poor analogy — there are activities and capabilities that can only be obtained from various points in space that cannot be done from Antarctica (or anywhere else on Earth). The point of humans moving beyond LEO is to bring the unique capabilities that people and machines working together can offer to those points in space where the various activities can be done.

Besides, the economic development of Antarctica is prohibited by the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctica Treaty. In essence, the entire continent is a science park.

True

From Winchell Chung’s Atomic Rockets “MacGuffinite is some incredibly valuable commodity only available in space which must be harvested by a human being that will provide an economic motive for a manned presence in space.”

I had told Winchell that the lunar MacGuffinite is water. His reply was that the Pacific ocean had plenty of water.

Water in the Pacific is at the bottom of earth’s gravity well and does nothing to break the tyranny of the rocket equation. Given earth’s surface as the sole source of propellant, we’re stuck with 8 or 9 delta V budgets just to get to orbit. If we want to go beyond LEO, we’re stuck with even higher delta V budgets.

Big delta V budgets mandate very difficult mass fractions which boosts expense. See http://hopsblog-hop.blogspot.com/2012/08/mf-is-mofo-tyranny-of-rocket-equation_21.html . In particular, the very difficult mass fractions have so far made multi-stage expendables the way to go.

Propellant at EML1 or EML2 would be a huge game changer for enabling economic transportation. Not only for deep space destinations like asteroids or Mars, but for cislunar space as well. Easier access to our orbital assets is a large and immediate economic benefit. Easier access to asteroidal PGMs and other resources is a potential benefit down the road. So yes, space does have economic incentives Antarctica lacks.

I was very disappointed with Chung’s “plenty of water in the Pacific Ocean” comment. From his pages it’s clear he’s familiar with the rocket equation. What he doesn’t seem to have a grasp on is the possibility of breaking delta V budgets into smaller legs. Chung’s delta V charts give figures for low circular planetary orbits to low circular orbits. Or from planet surface to planet surface. A disappointingly large number of people still haven’t grokked the benefits of a staging platform in high lunar orbit.

Interesting. One question more for reinforcement than clarification. The below statement makes it seem that a desire on the part of President Bush to note the wide ranging long range goals of the policy unintentionally (at least on the Presidents part) ended up subverting the actual initial goals of the policy. Is that correct?

“However, the mission of the VSE became muddled and Mars advocacy was the reason. Although President Bush clearly understood the purpose and value of learning how to create new capability by going to the Moon, he wanted to demonstrate its wider relevance by including Mars as a goal in (not the goal of) the new VSE.”

Dennis Wingo’s post also brings up an interesting point”

“The first fight that should have never happened was the fight between the idea of lunar Sorties and a lunar outpost. Our friend Harrison Schmidt was adamant about sorties as the best way to fully explore the Moon and eventually find an outpost.”

I was not involved “in the early VSE era” but was involved in Constellation Systems from early 2007 until its shut down. There was still a debate going on over requirements to be put in the Constellation Systems Architecture Requirements Document (CARD) about whether sorties or a base was the primary objective and many in the science community were still arguing for sorties.

I notice however that Schmidt now has out the proposal at the link below:

http://americasuncommonsense.com/blog/category/science-engineering/space-policy/4-new-proposal-for-nasa/

Note the mission statement for the proposed new agency:

“Provide the People of the United States of America, as national security and economic interests demand, with the necessary infrastructure, entrepreneurial partnerships, and human and robotic operational capability to settle the Moon, utilize lunar resources, scientifically explore and settle Mars and other deep space destinations, and, if necessary, divert significant Earth-impacting objects.”

Does this represent a change in position on his part?

Joe,

a desire on the part of President Bush to note the wide ranging long range goals of the policy unintentionally (at least on the Presidents part) ended up subverting the actual initial goals of the policy. Is that correct?

The Mars mania of the agency long pre-dated the VSE. I would not put it the way you have above — I think that President Bush wanted to go to Mars as well as the Moon, but in a sane, rational and affordable way. He fully understood that “Apollo to Mars” was not the way to conduct this program and accepted the value of creating a cislunar infrastructure first. But the mere mention of Mars in the Presidential speech did not cause the VSE to de-rail — that was done through the concerted efforts of certain people within and outside of NASA.

Does this represent a change in position on his [Jack Schmitt’s] part?

As far as I know, Jack has always supported a permanent presence on the Moon. But as Chairman of the NASA Advisory Council, he advocated a series of sortie missions to various places around the Moon to advance knowledge and to optimally select the best base site. The move away from outpost to sortie had several significant (and unfortunate) side effects — it made the whole enterprise seem more “Apollo-like” than anything new and different (“Been there, done that!”) and it dissipated surface resources so that new capability could not be built up. It added significantly to the total cost as well.

Wouldn’t it have been more sensible to use robotic observations to pick the best site for the first lunar base?

If you look at the Griffin era Constellation you can easily see what the preference was. A great deal of the problems with getting even the biggest version of the Ares VI to meet its Trans Lunar Injection (TLI) mass was the requirement to have the Altair lander. This huge lander had to not only do the Lunar Orbit insertion burn because the Ares 1 could not loft a more capable Orion, it had requirements to basically be a sortie class vehicle in an outpost strategy. That vehicle could have been far simpler and lighter if it was to take humans to and from lunar orbit.

When Griffin was asked about what activities would be on the Moon for the crew his answer was that his job was to build the rocket and that other people could figure that part out.

A lunar architecture has to work from the goal backward to the systems needed to implement the goal. The Ares V and VI were always designed with a forward view toward Mars. They simply were not needed for the Moon and indeed a Shuttle C type Shuttle derived cargo lifter could be flying today and be ready to carry humans and cargo to the Moon.

Ares VI?

Yep, toward the end they were adding at sixth RS-25 first stage and a five and a half segment booster and were still not getting their required TLI mass. How easily we forget and the Internet’s memory is selective.

“The Ares V and VI were always designed with a forward view toward Mars.”

Indeed. Even the name of the rocket is straight from Zubrin’s “The Case For Mars”.

Regardless, there will be those who try to hang this albatross on the neck of lunar advocates.

I think what many of you bring up is the lack of control over program requirements for Constellation. That is the role of the program manager.

I can tell you from my experience as a requirements manager early in the Shuttle years, that discussion, contention and outlyers who needed to be reined in was frequent and routine. The program managers frequently had to ask the various contenders, “don’t feed me all this garbage, tell me what decision I need to make”. I saw meetings almost every week where a second discussion had to address what had not been resolved in an earlier meeting. A great program manager did not sit still for long contentious discussions. He did not have the time.

In my role as a requirements manager my job was to make certain after program control boards which included both requirements control board and cost limit review boards, to know the requirements made sense, that the direction was clear, to identify when a decision made in the open forum was not clear or if it was ambiguous, to follow up with the different organization’s managers to gain evidence and make certain that all the parties were playing to the decision that had been made, and where decisions were not being carried out, to warn people, including the program manager, that the contention had not been resolved or that there were still people or organizations working to a different baseline. My job was to observe, understand and communicate. My job was to make sure the requirements were clear and unambiguous and being followed. The program manager’s job was to make sure he could achieve the program’s goals.

So what Paul Spudis, Dennis Wingo and others are pointing out, is there was no control established for Constellation. Maybe once Griffin came in, he took over the management of the program? Someone has to have the kahunas to speak up and make the decision or else take action. If the program manager is not permitted to control their program, that requires action too-maybe even stepping down to make sure the superiors fully understand the program cannot be managed with their interference.

Its easy to place blame or identify undue influences by Jack Schmitt or others, but the buck stops with the program manager and his requirements manager-a reason why requirements is usually linked to budget and cost control.

In Constellation, Program Management and requirements control was lacking. This was not the way to run a successful effort.

GH,

I think that the issue here was well above the program manager level. I will be describing the reasons for my belief in future posts.

Agreed.

There was a whole set of presentations in 2008 at the 40th anniversary of the launch of Explorer 1 in Huntsville. These presentations were from some of the surviving Redstone and Saturn Era engineers related to what made their era a success.

One of these presentations was by Rein Ise, who worked at MSFC for over 40 years and was a systems engineer during the Apollo era. He put up a picture showing 14 men sitting around a table. These men included Von Braun, Art Rudolf, Stuhlinger, and others who were the top people around Von Braun.

What Rein said was that during the Apollo era when a critical decision was needed and presented to these 14 men that the decision that would come from these guys were the right ones, or these 14 men would know who to call to get the right answer and it would be the right answer for whatever problem or decision that would be needed.

What Rein said (and he was consulting to MSFC during the Ares development) is that the decisions were being made in Washington and there were no equivalent to the 14 men from the Apollo era to make the right decisions.

That, at the end of the day, was the problem.

Similar situation in the early years of Shuttle. Everyone at the table had serious technical development experience going back to WWII, X-Planes, Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab. They each had decades of experience in their respective areas of Engineering, Systems Integration, Flight Crew, Payloads, Mission Ops, Med Ops, SR&QA. If you do not have well experienced, recognized, respected knowledgeable people making the decisions, then you don’t have a program.

You know, the funny thing about the development of the STS system is that it was at the end of the day only about 15% over budget. People screamed about that then, it would be applauded today.

The biggest problem with the AresI I/V architecture was that it delayed development of the heavy lift vehicle until the Ares I was completed. So there was never any serious funding for the Ares V core stage, departure stage, and the Altair.

The biggest advantage of the SLS program is that the heavy lift rocket is being developed immediately.

The Altair vehicle’s most serious flaw, IMO, was the fact that it wasn’t designed to be a simple single stage reusable vehicle capable of taking advantage of lunar oxygen and hydrogen resources.

A large reusable lunar lander could utilize lunar hydrogen and oxygen to transport astronauts from the lunar surface all the way to Earth orbit (utilizing aerobraking) and back to the lunar surface– all on a single tank of lunar fuel. Even if the engines had to be replaced once in awhile, such a reusable lunar people shuttle could dramatically reduce the cost of transporting people to the lunar surface and back to Earth orbit and even allow commercial crew vehicles to easily transport tourist to such lunar shuttles for tourist trips to the Moon.

Producing lunar water changes everything!

Marcel F. Williams

“A large reusable lunar lander could utilize lunar hydrogen and oxygen to transport astronauts from the lunar surface all the way to Earth orbit (utilizing aerobraking) and back to the lunar surface– all on a single tank of lunar fuel.”

Lunar surface to LEO and back is almost 9 km/s (assuming 3 km/s shed by aerobraking). About the same as earth surface to LEO. A 9 km/s delta V budget makes for a very difficult mass fraction. And the dry mass fraction must also include TPS for the 3 km/s that is shed by aerobraking.

Much more doable is a reusable lunar lander that moves between the lunar surface and EML1. Then another ferry that moves between EML1 and LEO. This makes for delta V budgets in the neighborhood of 4 or 5 km/s. A much less challenging mass fraction!

Even more doable is a single stage to orbit (Low Lunar Orbit) system that would require even less delta V and a LOT less in terms of support equipment to keep a crew alive for the trip to and from EML-X.

I am really beginning to like the Gilruith idea of the open cockpit lander which would further reduce the requirements and result in a system with a hell of a view to boot!

Dennis Ray Wingo commented on The Vision for Space Exploration: A Brief History (Part 1).

“Even more doable is a single stage to orbit (Low Lunar Orbit) system that would require even less delta V and a LOT less in terms of support equipment to keep a crew alive for the trip to and from EML-X. I am really beginning to like the Gilruith idea of the open cockpit lander which would further reduce the requirements and result in a system with a hell of a view to boot!”

It would certainly provide a “hell of a view to boot” but it would also create a number of interesting problems when the time came to transfer the crew to the (presumably) pressurized orbiting vehicle. Since the crew would have to be wearing EVA Suits:

– How would the open cabin lander be secured to the orbiting vehicle?

– Would the crew be on umbilical or be using Portable Life Support Systems (PLSS).

– If the orbiting vehicle is designed anything like the Orion (or any of the commercial crew vehicles) the only access hatches will not allow the surface area for transfer.

– If umbilicals were to be used a fairly complicated choreography of mating/demating umbilicals would be required (I worked on this for Constellation Systems – as an emergency procedure if they could not get a good pressure seal between the two vehicles) and that is not something anyone would want to do on a routine basis.

What about a single stage from lunar surface to LEO and back but which would refuel at a depot at L1 going and maybe returning (to the Moon). It would still need to lug the heat shield up and down from the lunar surface but it means no transferring of crew and perhaps a straight shot from Moon to LEO (no stops) in a medical emergency.

Also, what about humans not having their own landers but traveling on the same craft that had transported cargo (automated landing but the astronauts could take over in a pinch)?

Also, it would mean one less vehicle to develop and test.

Doug,

It would still need to lug the heat shield up and down from the lunar surface but it means no transferring of crew and perhaps a straight shot from Moon to LEO (no stops) in a medical emergency.

Stopping at the L-points or low lunar orbit to transfer crew does not significantly add to the transit time from the Moon to the Earth. There are significant mass penalties to lug the Earth-return heat shield down to the lunar surface and back.

what about humans not having their own landers but traveling on the same craft that had transported cargo

No problem in principle — it just decreases your possible landed payload on the Moon. It’s not simply the mass of the crew — it’s also their necessary life support systems that reduce the useable payload.

Yep, toward the end they were adding at sixth RS-25 first stage and a five and a half segment booster and were still not getting their required TLI mass. How easily we forget and the Internet’s memory is selective.

There never was an Ares VI and the core engines for Ares V were RS-68’s, not SSME’s. I worked the program.

Here is the NASA Watch article on the study.

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2008/06/does-ares-v-i-vi.html

There never was an Ares VI and the core engines for Ares V were RS-68′s, not SSME’s. I worked the program.

Yep you are right about the engines, that was before coffee this morning but there was a concerted effort and serious consideration toward adding the sixth engine and the five and a half segment booster and they were still short of their TLI required mass.

Dennis Ray Wingo says: October 23, 2012 at 11:38 pm

“If you look at the Griffin era Constellation you can easily see what the preference was. A great deal of the problems with getting even the biggest version of the Ares VI to meet its Trans Lunar Injection (TLI) mass was the requirement to have the Altair lander. This huge lander had to not only do the Lunar Orbit insertion burn because the Ares 1 could not loft a more capable Orion, it had requirements to basically be a sortie class vehicle in an outpost strategy. That vehicle could have been far simpler and lighter if it was to take humans to and from lunar orbit.”

It is actually even more complicated than that.

– The launch architecture required that the Altair/Earth Departure Stage (EDS) be launched first and await the arrival in LEO of the Orion. Since there had to be a “loiter” time in LEO (in case the Orion launch had to be delayed) that caused the need for the EDS tankage to be oversized to allow for boil off.

– The launch architecture required that the Altair ascent stage house the docking system that was required to react the Trans lunar Injection Burn Loads. This minimized the mass (and available volume) of the ascent stage which is the thing you want to maximize for either a base or sortie strategy.

Joe, yea I heard about that. Another thing that I heard is that they never solved this problem as the loads were a lot higher than the APAS was designed to handle.

Dennis Ray Wingo says:

October 24, 2012 at 2:07 pm

You know, the funny thing about the development of the STS system is that it was at the end of the day only about 15% over budget. People screamed about that then, it would be applauded today.

Actually, I don’t think it was really over at all. Bob Thompson had anticipated development problems in a number of areas including the tiles and main engines and had asked for reserves which he did not get. When you consider the sophistication of what was being developed, I think they were under the planned and anticipated budget.

Its funny (maybe the real word is disheartening) to think about now. They’ve been working on Orion for 7 or 8 years now, which is a far less sophisticated vehicle and really contains essentially no new technology, and is tiny by comparison, and they are still 6-8 years from flying a real vehicle, and actually I don’t think they have done any work at all on the service module or its systems so the vehicle they’ve been designing is not fully functional. Shuttle got the go ahead in 1972, Enterprise flew five years later and the basic airframe and lots of the ancillary systems had been designed, certified and manufactured, and Columbia flew in about 9 years. The budget was seriously constrained throughout.

Its funny that with all of the discussion about Shuttles over the last couple of years, all you ever heard about was the astronauts. The people, like Thompson, who designed, developed and managed the Shuttle program were the real heroes and yet 99% of the people have never heard of them. Al Worden wrote in his book a great paragraph on the lack of real mental effort that it took to fly a mission, yet the astronauts are the only ones getting the recognition. NASA needs to put some serious attention back on the intellectual side otherwise they are going no place anytime soon.

Yea I remember reading about the lack of reserves, makes the story even sadder. If you look the time between the final contract award to Rockwell and the roll out of the Enterprise, four years seems like an instant in aerospace time.

I was at Oshkosh a few years ago and saw an information plaque that stated the U.S. government trained 250,000 aircraft mechanics alone during WWII. We built tens of thousands of airplanes and the supply chain that went with it.

You sound like you work in the industry so you know that our aerospace industry is little more than a rump of what it was in the 60’s and even 80’s….

We need to rebuild it from the ground up. Elon has the only company bringing any innovation to the issue of cost reduction in the launcher biz and while it is laudable, it is also telling.

Paul:

Thanks for giving us a better picture of the runup to the VSE announcement!!!

Nelson

Thanks for the added insight.

As perspective from the trenches at a NASA center at the time of the VSE, the excitement of going back to the moon never abated. Lunar exploration working groups sprouted up and everyone was rushing to become experts and proposed many research topics. In fact, this effort has morphed into a more general future exploration working group. At no time, did I see or hear anything that proposed making Mars the higher, more near-term goal.

Matt,

Yes and I am aware of and will attest to that. I met many good, competent people within the agency that were excited about the VSE and worked their butts off to see it accomplished. But there were also many in middle management who actively worked against it from the beginning. I am trying here to relate the story from my own perspective. I know that others will see some things differently, but I wanted to record some of these lesser known events before they get lost forever. Thanks for reading it and for your supportive comments.

Pingback: After the Vision: What Next? | Spudis Lunar Resources

Pingback: A History of the George W. Bush Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) by Paul Spudis | Spaceflight Chronicles

Pingback: Direction for Space Needed | Spudis Lunar Resources

Pingback: Cis-Lunar – “The Vision for Space Exploration” – Paul Spudis | Space Resources Extraction Technology, Inc.

Pingback: Buzz Moons Lunar Return | Spudis Lunar Resources Blog