Overblown? The 90-Day study, in a nutshell.

Broach the topic of the “90-Day Study” with almost any random person involved with space for more than 25 years and you’re likely to provoke a reaction akin to showing Dracula a crucifix. This document is now offered as a cautionary tale about what flows from a devastating report – a bloated, impenetrable disaster of transcendent magnitude that doomed President George H.W. Bush’s Space Exploration Initiative, the 1989 attempt to fashion a set of long-range strategic goals for America’s civil space program. Released to near universal disdain and condemnation, its dread name lives in infamy in space history circles.

To understand what is behind all this opprobrium, I’ll begin by describing the historical circumstances under which this report was written, followed by the reasons it took the form that it did and what truth, if any, lies in the rather overblown reaction to it described above.

Twenty years after our space program’s peak during the Apollo effort, and despite President Reagan’s initiation of the Space Station Freedom project in 1984, our space program was under fire. The tragic loss in January 1986 of the Space Shuttle Challenger with her crew of seven led to critical reappraisals of the nation’s human spaceflight program. The fact that the accident seemed to result from hubris and incompetence only increased the volume of criticism. In time-honored Washington fashion, it was thought that a committee of experts should examine our space program and recommend a long-range direction. As it turned out, such a group was finalizing its report and mere months from issuing their results. The National Commission on Space (a.k.a. the Paine Commission) report (May 1986) was a grand vision of orbiting space cities, lunar and martian bases, and human expansion into the Solar System. Its unfortunate timing – along with its marked science-fiction flavor – led it to be largely ignored by policy makers in government.

However, the Paine Commission was not the only group working to devise a new direction for space. Several parallel efforts to plot a future course for NASA were also underway, both within and outside the agency. Since the early 1980s, a movement to examine the potential benefits of a return to the Moon had been studied by a group at the NASA Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston. Simultaneously, another effort was studying human missions to Mars (there had been no missions of any kind to Mars since the Viking explorations of the mid-1970s). These two streams converged within the agency in the Office of Exploration, which conducted paper studies on how to advance human spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit. An internal NASA group chaired by astronaut Sally Ride released a report to the administrator in 1987 that outlined the possible benefits and approaches for a variety of these initiatives, including human missions to the Moon and Mars. This report and the variety of work being done by NASA and others outside the agency provided the backdrop for a Presidential decision.

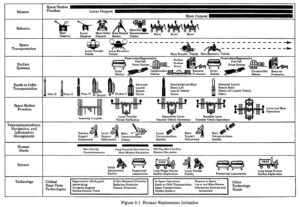

On July 20, 1989, the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the first landing on the Moon by Apollo 11, President George H.W. Bush gave a speech at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington that called for a return of people to the Moon – “this time to stay” – to be followed by a human mission to Mars. This policy proposal was dubbed the Human Exploration Initiative (HEI, later changed to “Space Exploration Initiative,” or SEI). The SEI included both robotic and human missions designed to extend human reach beyond low Earth orbit (LEO). SEI was largely the brainchild of the revived National Space Council, a White House-level policy group reporting to Vice-President Dan Quayle. Both Quayle and the Council were strong advocates of revitalizing the space program with a challenging set of goals. NASA was directed to produce a report within 90 days – a report that was to outline possible mission architectures and identify the technologies needed to accomplish those goals. The report effort was centered at JSC largely because that center’s Exploration Program Office had done the most detailed initial analyses of the problem. JSC Center Director Aaron Cohen was in charge of the study, with day-to-day operations headed up by engineer Mark Craig.

This intensive study effort took place during the months of August-October 1989, with the report issued late in November of that year. Upon its briefing and release to the National Space Council, the brickbats and invective began: unimaginative, bloated and “Battlestar Galactica approach” were just some of the descriptors attached to the report. Historical legend holds that because the report was so awful, the Space Council immediately engaged with a group at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to devise and offer a counter-strategy – the “Great Explorations” scheme of Lowell Wood that used inflatable spacecraft and was rumored to cost less than one-tenth the amount of money estimated for the heavily panned 90-Day Study approach.

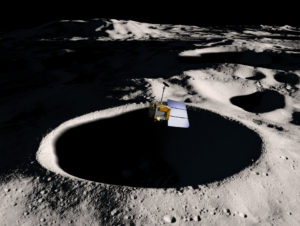

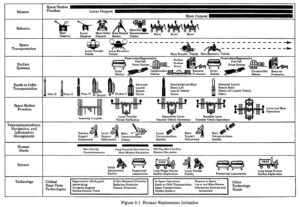

So just what did the 90-Day Study advocate? In brief, it described the vehicles and technologies needed to undertake human lunar and martian missions. It assumed the continued operation of the Space Shuttle, with new missions beyond LEO staged from Space Station Freedom (currently, the International Space Station). The new vehicles necessary for trans-LEO missions were outlined and described, including a Shuttle-derived heavy lift vehicle and a reusable cislunar transfer stage to send payloads to the Moon (using an aerobrake for Earth return). It also called for research on a nuclear powered Mars transfer stage and nuclear reactors for surface power systems on both the Moon and Mars. Extensive robotic precursor missions were outlined, including global surveys from orbit for the Moon and Mars, geophysical networks for the martian surface, a robotic sample return from Mars to certify the planet safe for human landings, and deployment of an infrastructure of communications satellites in martian orbit.

This list of assets was comprehensive, and yes, expensive. However, what was being described was nothing less than a permanent human foothold off-Earth. Moreover, this system of space assets and transportation infrastructure would be acquired and placed into operation over the coming three decades. The Space Council was disappointed that cheaper options were not presented, but it isn’t clear that had been part of the mandate for the study that the Council ordered from NASA. In contrast to claims that no architectural options were presented, five “Reference Approaches” were described that varied the phasing and dates of initial operational capability for the lunar base and Mars mission. In this regard, the biggest criticism of the report is that it took President Bush’s SEI speech as its policy guidance – “back to the Moon to stay and then to Mars.” This seems a strange criticism of a report – that it followed a directive given by the President.

Knowing how the 90-Day Report came about and how it was received, what is so objectionable about the report? As I read it, it outlined a step-wise, incremental approach to conducting lunar and martian missions, whereby existing assets are incorporated – employing continuity of purpose to build sustainability – and not discarded. Shuttle and Station would both support the missions beyond LEO and become integral parts of the spaceflight system. I contend that the architectural framework laid out in the 90-Day Study is exactly how we should approach going to the Moon and conducting missions to Mars. The report was criticized on the one hand for being “old school” and unimaginative in its use of proven technology, but then simultaneously criticized as taking too much risk in its advocacy of some advanced technologies, such as nuclear thermal propulsion and aerobraking into martian orbit.

So which is it – too Buck Rogers or too stodgy?

I can agree with the criticism that the architectural details of the report contained a lot of featherbedding by various widget-makers throughout the agency, but there was nothing in it that a good scrub by some hard-nosed systems engineers could not have fixed. Yes, it was Christmas-treed, but by looking past those superfluous (and expected) tinsel-hanging efforts, one sees good roots and branches beneath. The basic approach harkened back to the original von Braun architecture – shuttle, station, Moon tug, Mars spacecraft, a stepwise, incremental, cumulative progression to ever-farther regions of the Solar System. In contrast to some opinions, the technical approach laid out in the 90-Day Study was the very antithesis of the Apollo approach – the “all-up”, single-shot, self-contained missions to dash somewhere, plant a flag, and return, only to learn that your program’s been cancelled the day after your ticker-tape parade.

The cost numbers associated with the plan outlined by the 90-Day Study are subject to much confusion. The report itself contains no cost numbers whatsoever, the decision having been to include the estimates in a separate document, presumably on the fear that they would be misinterpreted (which happened). The numbers came from two different cost estimation models (then in use by JSC and NASA Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville) and ran to about $470 to $540 billion (FY1990 dollars), over a 30-year period of execution. These numbers included a 55% reserve for unexpected difficulties or accidents. While such budget numbers are substantial (the agency budget in those years was about $15 billion/year), spending such sums on NASA would still not have exceeded about 1.5% of the federal budget – this at a time when massive cuts in defense spending associated with the alleged “peace dividend” produced by the end of the Cold War were looming. Such a sum of money would have been about the same amount spent by the Department of Energy during this 30-year period. The idea that we “could not afford it” is simply ludicrous, especially as one motivation for devising the SEI in the first place was to partly maintain the industrial-technical infrastructure used to defeat the Soviet Union.

In the historical telling, the story goes that upon receipt of the 90-Day Study, the Space Council was so aghast that it sent the report to the National Research Council (NRC) for evaluation (and presumably, dissection). If the thought was that the NRC would trash it, such hope was misplaced. The NRC evaluation, while not uncritical of some details, largely acknowledges that the 90-Day Study offered a reasonable, relatively low risk approach to carry out the Presidential mandate. The White House then set up an “outreach” program, asking for the best technological ideas from many sources in order to show just how off-base the 90-Day Study was. A special group was gathered to evaluate these ideas – the “Synthesis Group” led by astronaut Tom Stafford (of which I was a member). After a year of synthesis and analysis, the group issued its findings: there are no “magic beans” technologies. To carry out the President’s Moon-Mars initiative, heavy lift vehicles, nuclear propulsion, extensive robotic precursor missions and many other items found on the checklist of the “overblown” 90-Day Study, were needed.

What about Livermore’s “Great Explorations” idea? The use of inflatable vehicles for human spaceflight doesn’t actually solve the fundamental problem of trans-LEO missions: most of the mass of the vehicle on departure consists of propellant, not habitats or transit vehicles. Moreover, inflatables have their own technical issues. Interior supporting structures are complex mechanisms and potential fail-points during deployment in space. The real problem solved by inflatable spacecraft is not mass, but payload volume – in the 1990s, large diameter modules could not fit on existing expendable launch vehicles or inside the payload bay of the Shuttle. Supposedly, by using inflatables, we would avoid the huge expense of developing a new heavy lift vehicle. But even this criticism is not valid, in that development of the unmanned Shuttle side mount launch vehicle would have solved this problem at relatively low cost (most of the then-existing infrastructure could be used), as well as providing a way to get massive pieces into orbit in single chunks.

So now, 25 years after the release of the “disastrous” 90-Day Study, and in light of current events, this study deserves another look. It is not a perfect document, containing some superfluous elements and questionable cost estimates, but its basic architecture uses exactly the type of incremental, stepwise, cumulative approach we need (and more and more are calling for) if we are ever to build a sustainable deep space transportation system. One final aspect of the report is notable: the 90-Day Study was the first agency architecture to incorporate resource utilization (ISRU) – specifically, the production of oxygen from lunar regolith (oxygen is 4/5 of the mass of the total propellant load in a LOX-hydrogen system). This resource utilization aspect of the 90-Day plan was incorporated prior to any knowledge of the existence of lunar polar ice (a game changer that would have been soon discovered anyway from the robotic precursor missions planned as part of the SEI). So once again, the 90-Day Study is, in many ways, well in advance of current plans.

I urge you to read the 90-Day Report and judge its merits and faults for yourself. It’s tragic that so much written about it inaccurately describes its content, or at a minimum, fails to provide any historical context for why the report advocated certain approaches. It is remembered as a despised, failed report, rejected by those who requested it and to this day, misunderstood through ignorance of the facts. It contained the bad news (and nobody likes to receive that) that there are no magic beans to climb to the stars – it will require a variety of complex, difficult and (yes) expensive pieces to establish the spacefaring system that we need. Inflatable spacecraft were the magic beans of the 1990’s space program – today’s space program has its own version of them. The cold hard realities of human spaceflight cannot be denied and the truth of that always comes out in the end.