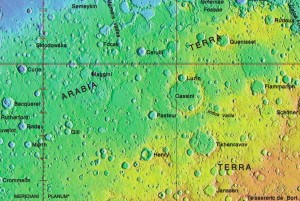

The cratered highlands of Mars — so few names, so many holes (U.S. Geological Survey topographic map)

Step right up and name that crater or mountain or molehill or patera (a fancy name for a saucer-like depression on Mars or Io)! I mean, why not? You’re a person, right? You have rights! Demand them! Go name that crater. You are free to name anything, anywhere in the universe. Many people have. Of course, no one has to use it – who will even know of its existence? That’s not what you had in mind, you say? But if you fork over cash to have something named after you (or a family member, a pet or your favorite burger joint) certainly it would have more credibility. Right? After all, some might claim that’s essentially what the International Astronomical Union (IAU) Nomenclature Committee is all about – a group of volunteer scientists, following agreed upon rules, assigning names to extraterrestrial features.

You might question the right of the IAU to make these decisions. Why wouldn’t your name, duly purchased and recorded on a web site, garner proper recognition and instant stature? It may well come to pass that sometime in the future, extraterrestrial bodies may be occupied by local populations who will then assume the right to name geographic features as they see fit (as we do here on Earth). But for now, scientists use this scheme because they are the ones using the planetary nomenclature. So, before you open your wallet, let me explain a bit of history about how and why landforms are named.

A key point about nomenclature is that it has no value unless it is standardized. Nomenclature is primarily for the convenience of researchers and scientists who work on those objects – they need to refer to some geographic location when discussing process or history. Planetary nomenclature serves the same purpose on extraterrestrial bodies that it serves on Earth – a shorthand way to refer to a locale without having to specify exact coordinates that a reader would have to look up on a map or globe. The object of nomenclature is to devise a shorthand that instantly creates a mental image of a location; that mass of knowledge must (at least partly) already reside in the mind of the reader. The gradual accumulation of such knowledge is only possible because scientists (who work and study these locales) have agreed among themselves to use a standard scheme of nomenclature.

To bring some order to the chaos, the scientific community organized the IAU nomenclature committees. These committees use agreed upon rules to create banks of names for surface features, to which they are assigned as needed. The rules are designed to assign different classes of names for differing categories of landforms, and different planets and satellites. For example, the Moon (the first object to have its surface features named) is somewhat of a patchwork, reflecting its complex heritage. Lunar craters are named for deceased scientists, engineers and explorers. To have a feature named for someone, that person must have made a significant contribution to knowledge or human achievement, and have been dead for three years. Later innovations to this scheme for the planets, reserves different classes of names for different objects. For example, features on Mercury are named for artists, while small features on Venus are named for famous women. Logically, craters on Mars (the planet named for the Roman god of war) should be given the names of famous military figures, but the delicate sensibilities of academia overruled that eminently logical suggestion. So Mars craters (like those on the Moon) are named for scientists and engineers who have contributed to the exploration of Mars.

I don’t claim that this process has always been logical. Nonetheless, this system – with all of its flaws – has well served the scientific and exploration community for many years. When the IAU system stumbles and imposes some egregiously stupid edict, the user community can simply ignore them and continue to use the older, existing names. This happened in the mid-1970s, when hundreds of lunar names were discarded and new names assigned with no apparent thought or logic. Active lunar scientists continued to use the older names in defiance of the IAU edict. The IAU finally and quietly surrendered twenty years later and the old naming system of primary and satellite craters was preserved.

Despite the passage of time and the assignment of names to many landforms in space, it seems all that unnamed space real estate is too big an opportunity for some to pass up. So a company called Uwingu is offering to affix the name of your choice to a feature of your choice (or one they’ll choose) on Mars, for a fee. The purchased name will be affixed to the crater and maintained in a database on the Uwingu web site. Naming rights for features currently holding IAU names are not for “sale.” Currently up on the block however, is a large inventory of small, as yet unnamed craters on Mars (500,000) – mountains, hills and canyons will be offered for “sale” soon. The cost of crater names varies according to the prominence of the feature you select. Our local Solar System not to your liking? Then for $4.99 you can nominate a name for an exoplanet. If it gets 1000 “votes” (at $0.99 per vote), your name will be affixed to your adopted exoplanet.

That’s what you’re buying. No one is obligated to use your name or even to look it up. It won’t appear on any map product except those that Uwingu may produce. If you’re good with that, go forth and more power to you. But don’t be upset because no one uses your bought and paid for name. Uwingu informs buyers that their purchased names are not recognized by NASA or other space agencies – “yet” (implying that might change in the future). The site goes on to advise that for scientific papers, you and others are free to “reference them using their citation number in Name Database Registry.”

My sense is that people do this because they imagine they will achieve an immortality of sorts by having their name affixed to some extraterrestrial object. Having it compiled in some web site database adds authenticity to the process, regardless of whether anyone consults that data or not. But you don’t need to pay Uwingu to do this – there’s nothing stopping you from putting your name on features on your own web site. Eventually, someone may click on it (assuming you continue to pay for the web hosting).

I find this new Uwingu scheme offensive because it preys on the ignorance and trust of the general public. Most people don’t know the reasons for the procedures of planetary nomenclature or the agreed upon rules. They like the idea of having their name associated with something, so they buy the website pitch. A similar idea was unveiled a few years ago with something called the International Star Registry, which would name, not simply some dinky crater after you, but a star – possibly one that’s at the center of an entire system of planets! Of course, any possible inhabitants of that system would be blissfully unaware of your existence, but it might certainly enhance your self-esteem.

Caveat Emptor!

I believe that there are hundreds of thousands of craters on the lunar surface that are at least one kilometer in diameter or larger. And I can see the logic of having the IAU naming such large surface features.

But selling the naming rights to craters– smaller than one kilometer– on the lunar surface could be a way of creating the first commercial enterprise for the owners of the Moon (the people of the Earth according to the Outer Space Treaty). The IAU could still have the right to reject any names that are offensive or inappropriate.

You could perhaps charge $1 million to name a lunar crater between 100 meters to 1 kilometer in diameter; $100,000 for craters between 10 meters to 100 meters; $10,000 for craters between 1 meter to 10 meters. So individuals or organizations would have to spend some– serious money– in order to name these craters. Again, the IAU would have the right to reject any name thought to be offensive or inappropriate. The revenue from this lunar naming enterprise could be divided equally amongst every nation on Earth which would of course favor those nations with the smallest human populations.

But this might catalyze a great deal of interest by all of the nations of the Earth for the future commercialization of the Moon by humans on the lunar surface. It might also be a good investment if a lunar company decides to settle an area where there’s a crater that you named– if they desired purchase the right to– rename– the crater from you:-)

Marcel

Like the idea, Marcel. You could have also real naming rights to unnamed stars officially recognized by the IAU. This could be used to raise funds for astronomy projects.

Bob Clark

Great article and I fully agree. I’m working on new topographic map of Mars and I really do not intend to use commercial names in it.

Again, I would argue that major features on Mars, including craters that are at least 1 kilometer in diameter, should be exclusively named by the IAU.

But purchasing the rights to name craters less than a kilometer in diameter and other small features on the Martian surface is an opportunity to begin to generate extraterrestrial revenue for every nation on Earth and to capture the imagination of the general public.

We need to have a lot more people thinking about humanity’s future in the Solar System. And this would be a way for them to participate very early on with serious money out of their own pockets!

Marcel

Marcel,

This is beside the main point — the “rights” to name a crater on Mars (or anywhere else) are not Uwingu’s to sell. Yet their pitch to the general public on their web site implies that they are. No one will ever use the names that you buy to refer to those craters.

I agree. Since the Moon is part of the common heritage of humankind (mankind) according to those nations that have signed the Outer Space Treaty, Uwingu really has no right to do this.

But if revenue was to be generated– in the future– from naming small features (less than a kilometer in diameter) on the Moon, Mars, Mercury, etc., I think even this would have to go through the UN according to the Outer Space Treaty:

“…..4. States Parties have the right to exploration and use of the Moon without discrimination of any kind, on the basis of equality and in accordance with international law and the terms of this Agreement.

5. States Parties to this Agreement hereby undertake to establish an international regime, including appropriate procedures, to govern the exploitation of the natural resources of the Moon as such exploitation is about to become feasible. This provision shall be implemented in accordance with article 18 of this Agreement.”

Since I would consider selling names (but not owning the area) to tiny craters on the Moon as part of– lunar exploitation– laws regulating such practices would have to go through an agreement amongst nations who have signed the Outer Space Treaty.

Plus I can’t imagine the IAU having the time or even the desire to name– all– of the tiny craters (between one meter to less than a kilometer in diameter) on the entire lunar surface– except maybe for some special areas of aesthetic or historical significance.

Marcel

Pingback: Who Should Name the Craters on Mars, You or Astronomers? | Techbait Tech News

Pingback: Who Should Name the Craters on Mars, You or Astronomers? | Wired