Two articles regarding the never-ending debate over our national space program recently drew my attention. One, published by Hearst Newspapers, discusses the current policy confusion in space, particularly in regard to the different versions of the next NASA Authorization Bill currently before Congress. Another article highlights (inadvertently) the amount of federal money spent on civil space. Both pieces, though different in scope and intent, bring into sharp focus the dilemma facing our space program.

With the recent two-week partial “shutdown” and current focus on the Health Care Initiative, national attention is diverted from other aspects of the government. Currently, the document outlining Congressional strategic directions for the agency – the next NASA Authorization Bill – remains stagnant in the bowels of committee structure, blocked by the now too-familiar chaotic process that passing the annual federal budget has become.

Last summer, both House and Senate Subcommittees on Space drafted new Authorizations for NASA. The House version keeps a strict funding limit under the existing budget “sequester” (at a level of approximately $16.6 billion per year) and lays out a path that makes the Moon and cislunar space the next goal for human spaceflight. Significantly, the House bill specifically forbids the agency from pursuing the administration’s proposed “haul asteroid” mission, in which a meters-sized near-Earth object is bagged and brought into lunar orbit, where a human crew in the new Orion spacecraft would rendezvous with and examine it for a brief period. The Senate version of the bill authorizes more money for the agency (~$18 billion per year) but does not prohibit the haul asteroid mission – in fact, the Senate bill is silent about any mission beyond low Earth orbit at all. Both bills would continue to fund the agency’s new SLS launch vehicle and Orion spacecraft. Ordinarily these bills would be sent to the respective chamber floors for a vote and then sent to conference, where the differences between the two versions would be sorted out.

Conventional wisdom holds that under either authorization, NASA would get less money than it needs to carry out all of the missions and policy directives in its portfolio. Most famously, the 2009 Augustine report claimed that a budget increase of roughly $3 billion per year was needed to fully execute the then-existing goal of lunar return. This number has gained wide “rule-of-thumb” currency in space policy circles and has been used as both a rallying cry to garner support for more funding and as an excuse for why the agency cannot seem to make any significant progress beyond (barely) maintaining the International Space Station.

There are two ways to approach the issue of space spending. One is to ask the question, “Are we funding the agency at the right level?” (Which assumes that NASA is – broadly speaking – going in the right direction and the rate of progress is really a function of the amount of money we spend on it.) A slightly different approach asks instead, “What are we attempting and is there a path by which we can reach that goal?” (This questions the current direction and instead seeks to envision alternative paths to space achievement.)

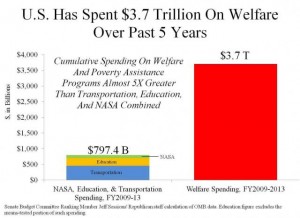

Many polls show that large segments of the public are convinced that NASA gets much more money than many other government agencies, particularly in comparison with social welfare programs. A recent press release from the Senate Appropriations Committee illustrates dramatically that such is not the case. In fact, the combined budgets of NASA, and the Departments of Transportation and Education are dwarfed by the amounts spent on welfare; the combined total for these three entities collectively constitute about one fifth the cumulative, discretionary amount spent on welfare over the last five years. Even more telling is that within that random grouping with Education and Transportation (see figure), the space agency’s budget is but a miniscule fraction of the aggregate amount of these three diverse federal enterprises. It is important to emphasize that this is all discretionary spending; entitlements (a much larger fraction of federal spending) are not included in this analysis.

The budget allocation for NASA is now and has been for many years about one-half of one percent of total discretionary spending. By virtue of this spending level having been maintained for the last thirty years, this annual amount of appropriated money apparently is politically sustainable. In fact, flat level funding was integral in the planning of the original Vision for Space Exploration – by cleverly spending what we would likely get for space, it would be possible (over time) to build-up a permanent and lasting capability. A predicate of this idea was that we had a notion of the direction we wanted to go – that we could systematically pursue that direction regardless of the rate of progress in any given year.

Unfortunately, the idea of an incremental, sustainable approach was lost in the implementation of the VSE, as I have previously discussed on this blog and elsewhere. We seem wedded to the idea of a civil space program as a venue for entertainment, wherein each mission must be something “new,” “spectacular” and “trailblazing.” Even now, this mindset dominates the national discussion, whereby a return to the Moon was abandoned because “we’ve been there” – a has-been stunt and the audience needs a new act. We’ve become trapped in a progressive space program of “firsts” and new thrills to “engage the public” and exhorted to “engage our touchy-feely side” rather than make logical judgments on the basis of cold facts. A tacit admission that this paradigm prevails is seen when the NASA Administrator claims in public discourse that we are doing the haul asteroid mission “because it’s all we can do” – he draws a blank when attempting to describe any possible benefits from it.

The real debate over space policy is not about destinations, it is about our national mindset and template of space operations. If the policy remains focused on performing public relations spectacles, we should not be surprised that until this “circus” folds its tent, only stunt missions will be proposed and flown.

I believe that human spaceflight has proven societal value, one whose potential is hinted at by the design and construction of the ISS, but a value not yet fully realized and exploited. We should strive for a human spaceflight program that gradually and incrementally builds capabilities over time – an extension of human reach beyond LEO into cislunar space. In such a mindset, the amount of money NASA receives becomes less significant and less disruptive. True enough, there is a budget point beyond which we cannot make any progress, but we are far away from such a level at $16 billion per year.

The National Academy panel currently examining the future of human spaceflight could serve a useful purpose by re-focusing the national debate over the civil space program by asking: “Which approach to space provides lasting value for money spent?” Instead of asking how we can “get to Mars” the quickest (for reasons that are both questionable and unlikely), the issue should be: “Can we build a lasting space transportation infrastructure – one that permits us to undertake any mission we can imagine – under existing budgetary limitations?” Answers to these questions will clearly mark the difference between cost and value – giving us either a ticket to the circus or a pathway to the stars.

Another excellent article Dr. Spudis!

The irony, of course, is that useful government programs like NASA that actually help to create wealth, employment, and technological progress in this country are demonized as wasteful government spending because of the appalling inefficiency of America’s welfare state. Whether or not we have a space program, most Americans are probably doomed to poverty over the next few decades unless we– dramatically reform– one of the most unnecessarily inefficient and costliest welfare states on the face of the Earth!

With its close proximity to the Earth, low gravity well, natural vacuum, abundant sunlight, and the immense wealth of essential industrial resources in its regolith, establishing a permanent outpost on the surface of the Moon has been the next logical step for the US since the end of the Apollo program. And polls that I’ve seen– over and over again– strongly suggest that most Americans who are interested in the space program actually understand this!

Supplying lunar water to the Earth-Moon Lagrange points through reusable cargo shuttles is the simplest and cheapest way to provide fuel and radiation shielding for reusable manned space vehicles destined for the orbits of Mars or Venus. Trying to supply fuel and mass shielding from Earth to LEO requires a substantially larger delta-v requirement than from the Moon. And launching vehicles from LEO to these interplanetary destinations also requires a substantially larger delta-v requirement than launching them from the Earth-Moon Lagrange points.

Establishing water production facilities on the Moon makes going to Mars a lot easier. And establishing a permanently manned outpost on the Moon should make it a lot easier to establish similar permanent manned outpost on the surface of Mars.

Permanent outpost on the Moon and Mars would allow robots to continuously and extensively explore all regions of these two worlds, returning their samples back to the manned outpost for eventual return to Earth.

A NASA manned spaceflight related budget that ranges between $7 to $10 billion a year over the next 25 years should be able to do this– as long as establishing a permanent presence on the Moon and on Mars are prioritized as NASA’s near term (the Moon) and long term (Mars) goals. A low $7 billion a year manned spaceflight related budget would probably make it longer and a little more expensive to achieve these goals– but it shouldn’t stop NASA from eventually reaching these goals.

But squandering NASA’s limited manned spaceflight budget with wasteful asteroid missions or by unnecessarily inflating the cost and extending the life of the very expensive $3 billion a year ISS LEO program beyond 2020 would guarantee that pioneering the Moon and Mars and the rest of the solar system by NASA and private US companies would probably be delayed by decades while American’s watch China and other foreign nations pioneering the Moon and beyond with logical and progressive manned space programs.

Marcel F. Williams

“Can we build a lasting space transportation infrastructure – one that permits us to undertake any mission we can imagine – under existing budgetary limitations?”

No. There is no cheap.

The space age ended at 2:25 p.m. EST on Dec. 19, 1972.

http://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_2121.html

It ended because of the cost of the Vietnam war.

The Shuttle was a failure because of the military requirements in the design.

The military space budget is bigger than NASA’s.

This is NOT a “Free Rider Problem” with Welfare recipients trapping us on Earth.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free_rider_problem

This IS a “Forced Rider Problem” with the easy money of cold war toys chosen over the hard money of building spaceships.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forced_rider_%28economics%29

It is so easy to blame it all on the bum cashing in his SSI check and buying crack.

It is a very unpopular view to attribute blame to corporate greed- but it is much closer to the truth.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corporate_welfare

Excerpt: In 1990 the federal government spent 4.7 billion dollars on all forms of international aid. Pollution control programs received 4.8 billion dollars of federal assistance while both secondary and elementary education were allotted only 8.4 billion dollars. More to the point, while more than 170 billion dollars is expended on assorted varieties of corporate welfare the federal government spends 11 billion dollars on Aid for Dependent Children. The most expensive means tested welfare program, Medicaid, costs the federal government 30 billion dollars a year or about half of the amount corporations receive each year through assorted tax breaks. S.S.I., the federal program for the disabled, receives 13 billion dollars while American businesses are given 17 billion in direct federal aid.[15]

But it is really the military that keeps us on Earth. Our space program is lined up in the boneyards filled with obsolete military hardware and piles of rubble in Afghanistan and Iraq. Our spaceships were traded for higher profit margins.

It is not lack of money- it is that the money is being spent on what creates larger shareholder checks.

The NASA human spaceflight budget could be tripled or quadrupled without anyone knowing the difference except the Military and their defense contractors who would have to build rockets to the Moon instead of weapons.

There is no cheap.

Yes, I know that you believe that (you must because you are continually saying it) but “cheap” is a relative term, not an absolute quality. What we need to do is to design a space program that can be implemented in an incremental manner such that we don’t require massive increases in the space budget, which won’t happen.

The simple fact is that out of a $3.8 trillion annual federal budget, the military gets about $673 billion; by my reckoning, that’s about 17.6% of the total spending. Various social programs (HHS, Education, Social Security) add up to over $2.2 trillion, or about 3.4 times the amount spent on the military, which protects not only ourselves but many other countries of the world via our various defense commitments.

The NASA human spaceflight budget could be tripled or quadrupled without anyone knowing the difference

Of course that simply isn’t true. If you believe otherwise, I suggest that you get yourself elected to Congress and try to implement your plan.

Most importantly, IMO, NASA needs a manned spaceflight budget that specifically prioritizes a water and fuel producing lunar outpost that utilizes reusable single stage LOX/LH2 vehicles with cryocooler and ULA IVF technology.

Reusable vehicles and fuel depots derived from reusable vehicles could be initially deployed by the SLS. Such a reusable infrastructure could be a key stepping stone towards extending Commercial Crew accessibility all the way to the lunar surface since reusable vehicles could be used as both orbital transfer vehicles between LEO and the Lagrange points (with aerobrakers) and as lunar landers operating between the lunar surface and the Earth-Moon Lagrange points.

Lagrange point fuel depots using lunar water could also be used to fuel reusable interplanetary vehicles derived from the SLS hydrogen tank, configured as a common bulkhead LOX/LH2 tank with cryocoolers and ULA IFV technology. Such a vehicle fueled with less than 300 tonnes of LOX/LH2 fuel could transport heavy water shielded habitat modules (100 to 300 tonnes) from the Earth-Moon Lagrange points to High Mars Orbit. Water shielding would be used to protect astronauts within twin rotating counterbalancing artificial gravity habitats (SLS fuel tank derived) from major solar events while also reducing annual cosmic radiation exposure to less than 20 Rem during the solar minimum.

Lunar habitat cost could also be reduced if they were derived from the 8.4 meter in diameter SLS fuel tank. Such large lightweight multilevel habitats (between 10 to 15 tonnes) could be instantly deployed by an SLS launched lunar cargo vehicle similar to the Altair descent stage.

Marcel F. Williams

Well, while we here in the US eat pizza bought with food stamps, and talk on our free cell phones, we can watch the Chinese and a real lunar exploration program land Chang’e 3 on the Moon in December on our big-screen TVs paid for with welfare wealth (which was likely borrowed from China in the first place). What a sad situation for ‘US’ to be in.

“Many polls show that large segments of the public are convinced that NASA gets much more money than many other government agencies, particularly in comparison with social welfare programs. A recent press release from the Senate Appropriations Committee illustrates dramatically that such is not the case.”

The graph is federal dollars.

Only federal dollars are spent on NASA.

Educational dollars are largely individual State funding.

Welfare is also has State funding.

So educational dollar of all government is somewhere around 1/2 trillion or

more per year. The Federal dollars on Education is insignificant and not

particularly needed. So one **could** 1/2 federal dollars on Education give NASA a lot more

money per year. I can think better department to cut than Education. I don’t think the

federal dollars on Education are actually making much effect on American Education-

it could having a net bad effect as much as any net good effect. But politically, cutting

Dept education could problem. Whereas obviously Federal welfare program could

could be more politically doable.

So, anyhow in terms of entire federal and state funding, all US government spending- a comparison with NASA spending would be more dramatic. Expect Welfare wouldn’t look at bad

vs money spend on Education.

It seems to me the best approach to NASA not having enough money is to have a low cost

lunar program with focus on exploration of lunar poles.

Rather than 40 or 80 billion lunar program, it should be 20 billion lunar program.

From the very beginning in terms of planning the focus should to keep it simple and short.

And about 1/2 of 20 billion being robotic.

Which doesn’t align with idea of doing a large variety and extensive amount of scientific

focus. Though there is a lot things about the Moon we want explore, NASA should focus

on finding minable lunar water deposit. And once NASA has found the better deposits

of lunar water deposit at the lunar poles, the lunar program would be completed.

And after such lunar program is finished we go back to current level of lunar exploration

which is sporadic. And NASA should then focus on manned Mars program- which will not

be like the lunar program, as it will take decades and it will be a large program [more than

100 billion].

In many ways the lunar program can be seen as step towards a Mars manned program.

And it seems that NASA should determine if the Moon has minable water before doing

a Mars Manned program.

It seems the key to getting this large amount of money for Manned Mars, is a very successful

lunar program.

And I would define a very successful lunar program as NASA planning the program, presenting

the plan to Congress, and NASA executing the program in the time and the budget it

planned. Thereby reversing the perception that NASA is unable to do anything large which

is on budget.

It seems to me that the larger the lunar program, the more likely the beginning of it is delayed.

And the lower the cost, the more eager Congress would be to fund it. Assuming the low cost

was realistic.

Interesting post today at Ezra Klein’s WaPo site (http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/challenges-have-dogged-obamas-health-plan-since-2010/2013/11/02/453fba42-426b-11e3-a624-41d661b0bb78_story.html) which makes me wonder if maybe the space community hasn’t dodged a bullet…

Short version: Political concerns (“What will the House Republicans say if we release that planning document?”) overrode efforts to actually firm up requirements and implement the President’s Healthcare program. Shorter yet: People screwed up managing what should have been a fairly straightforward middle-sized software engineering job.

The implication — for me anyhow — is that if the Obama administration had put its mitts on any reasonably ambitious space project and tried to push it forward from within the White House in JFK style that things would have gone very badly. Management skill strikes me as a much larger issue than whether Marburger or Holdren had a better vision of the future.

Correct me if I am wrong, but the 2013 appropriations only funds human spaceflight exploration -SLS and crew vehicle – to the tune of about $3 billion, not $16 billion. NASA is not just a space exploration agency, but also funds a great deal of space science and research along with robotic exploration. The ISS alone costs $4 billion which includes space support operations. So NASA does not remotely have $17 billion dollars on which to develop a lunar architecture. Even an incremental approach requires more than the current funding levels. I simply do not believe that you are being realistic about costs.

I simply do not believe that you are being realistic about costs.

Believe what you want to. I do not assume that the agency will get $16 billion per year to fund “exploration” (or “development of space faring capability”, as I prefer it). My point is that if you know where you are trying to go and what you are trying to do, you can plot a strategy that gets you there eventually.

The lunar architecture that Tony Lavoie and I published two years ago returned us to the Moon in about 9-10 years for less than $7 billion per year. After 16 years, we were producing more rocket propellant on the Moon than we were using to get there. Cut that budget allocation in half and you simply extend the schedule — if it takes 20 years to get to the Moon, so what? At least we’re moving in a consistent direction. Because we now know more about the lunar poles and its deposits than we did then, my suspicion is that we could get water production up and running sooner than previously estimated.

Of course, if it was decided to fund the agency at $1 per year, not much is possible (but that’s true for all other agency activities as well.) But we are not in that situation and are not likely to be. Moreover, at least some of what NASA does (Earth science) could be appropriately handed off to other agencies. And ISS will not last forever — wasn’t meant to.

So I do not think I am being unrealistic. I am asking for a space program that returns long-term societal value for public money spent. I realize that such a concept is not currently fashionable, but it should be.

This is an interesting issue. I am going to try to make three top level points (I hope without insulting anyone).

Point 1: In any engineering project there is an optimal funding level where maximum efficiency can be achieved (though that can be difficult to determine). That level for the plan proposed by Dr. Spudis and Tony Lavoie was estimated to be about $7 Billion/year. When you go below that level you will get less efficiency (that is you may spend less money in any one year, but the project will cost more overall). Additionally the time span to complete the project is not likely to only double with a halving of the yearly budget.

As an example the ISS was given in the 1990’s a $2.1 Billion/year budget (with no adjustments for inflation for years). That process eventually succeeded, but with many delays and “cost overruns”. One was for the automated water transfer system. When the system was eventually developed it showed that 2 more Remote Power Control Modules (RPCM’s) were required. Unfortunately (also to stay within the budget caps) the RPCM production line had been shut down. Consequently the unit cost of the new RPCM’s was very high producing both a delay and cost overruns (with the requisite snarky news articles). That type of thing was replicated many times across the program.

Point 2: There is also a minimum funding level below which nothing will be accomplished. I do not know where that level is (the $1 to $16 Billion range will certainly encompass it). Go below that and whatever amount you are spending (however low) is being wasted.

Point 3: The issue of funding stability also needs to be considered. In the early days of the Space Station (approximately 1985 – 1989) every year the program received a budget and estimated out year budgets for planning purposes. Then the next year it would all drastically change (all ways downward – of course). Consequently a significant portion of the next year would have to be spent replanning/rephrasing the entire project. As a result very little real progress would be made in those years.

So in order to have a successful program you have to:

– Determine the minimum funding level for the proposed project.

– Get political buy in to fund the project at (at least) that level (hopefully with cost of living adjustments).

– Get political buy in to fund the project consistently.

In a democracy that is a tall order even under optimal circumstances. Unfortunately the current circumstances (in terms of both economics and politics) are anything but optimal.

“The lunar architecture that Tony Lavoie and I published two years ago returned us to the Moon in about 9-10 years for less than $7 billion per year. After 16 years, we were producing more rocket propellant on the Moon than we were using to get there. Cut that budget allocation in half and you simply extend the schedule — if it takes 20 years to get to the Moon, so what?”

Maybe it will not get funded. maybe it will be funded and than year later it will be decided to not continue funding it.

A problem with Manned Mars, is will get something like a repeat of Apollo. And you get same problem with 16 years on the moon.

Plus you want 7 billion per year. NASA may want 10 billion per year, so this same reducing budget and requiring a longer time. So NASA may want 10, and they get 6 billion, and then 5 years later they could getting 4 billion or less.

I think you plan for less than 7 billion per year, and plan on it taking less 16 years. And because that total is less, maybe Congress will start it sooner than 9-10 years.

How make it cheaper? Don’t have NASA mine lunar water.

Not one should mine lunar water before exploring the Moon to determine where is the best areas

to mine water. Once this is known then it is possible to make a decision of whether mining lunar water is a good idea.

And it’s a good idea, if at some point it cost less to mine the water and make the rocket fuel

than the cost to ship the rocket fuel.

Now you could make the argument that it’s going to require a lot time and experience, and increase in ability to finally get to the point in time when mining lunar water is profitable.

OR after exploring the moon, what may find that it’s only takes a relatively short time [high capital cost in beginning] to get to point of it being profitable to mine water.

But such decision doesn’t need to made at this time, it can be made, after exploring the Moon.

So I say at least separate to a package you selling into two parts. I would prefer, that lunar water be commercial mined. Assume this is the starting premise.

I think if commercially mine it could actually profitably be done- just as any mining on Earth is done. And if the results of the exploration doesn’t indicate lunar water can be profitably mined,

this actually a good thing. Why mine anything which is not profitable?

But if you want NASA to mine lunar water, the congress at that time when it has gotten information

from exploration can then decide if the want to do part B. Or call it a different lunar program.

So instead of a congress doing the impossible of making decision for a Congress 10 or more years in the future, let the Congress make that choice in the future, when they have more facts available- because they do it anyway.

So you sell Congress on a cheaper program, and you say at some point congress can decide

which options it will take.

So the news cycle will be talking about the cost of the program which is which being past as bill.

The reporter will add costs they think it will costs. And NASA will add to cost of whatever is proposed, and when it’s executed it will probably cost more than planned.

So when all said and done it might actually cost 7 billion or much less per year. And maybe NASA will do it for 30 year, or maybe it will require less than 10 years.

If you had bothered to read our paper before you posted your comment, you might have discovered that the first phase in our proposed architecture is to fly robotic missions to survey and prospect both poles to locate and characterize the optimum locations for water extraction. Then we land demo-scale experiments, designed to let us understand how difficult resource processing on the Moon is in practice, so as to allow us to adjust the designs of the full-scale equipment to follow. Each step incrementally gathers the strategic knowledge needed to take the next step.

As for doing this “privately”, if someone can raise their own money and do it without government, bully for them and God-speed. But we are paying several billion dollars a year for a space program and I do not think it’s unreasonable to require that we get something of value for that investment. Why not have them find out if extracting and using lunar resources can be made to work from a systems point of view? For ensuring our long-term future in space, it makes more sense than questing for life on Mars.

I did bother read your paper. And it seem to me you are suggesting something that is a lower cost than any NASA plan I am aware. Also it’s quite detailed and sequential.

I would differ the approach, by having robotic and Manned being focused on finding minable water.

Or 80- 90% of total cost is finding where there is minable lunar water and perhaps limited program funds in demonstrational type mining techniques.

And I think the exploration Mars as something NASA should do.

Though I agree that search for life on Mars is over emphasized.

I think Mars manned exploration could something NASA should do [soon].

Though I might tend towards wanting NASA to do Manned exploration of Mercury, but as there seems to be little political interest in exploring Mercury,

and on top of that, no one even *appear* to think it possible.

I think Manned Mars should part of Lunar manned.

I say it this way, I would use lunar program to politically get to a Manned Mars.

Which I think is more important as compared to merely using infrastructure of Lunar program for Manned Mars.

And I see Manned Mars as one market for lunar water and lunar rocket fuel. So I see both as a symbiotic relationship. As I see commercial and NASA as symbiotic relationship.

Or said in different way, the only way that lunar water can be minable is by mining and making rocket fuel on the scale of 100 tonnes per year.

As far as I can see, this means lunar rocket fuel [or water] must be exported from the Moon.

And NASA’s budget limits the amount of lunar water which will be mined. Or NASA will mine “just enough”,

and just enough will not be enough.

“As for doing this “privately”, if someone can raise their own money and do it without government, bully for them and God-speed.”

I doubt such thing will occur within 10 years. And I would advise against say Bill Gates [or other billionaires] doing this. If for no other reason than there better things to do with the capital.

Though a billion dollars spent for determining whether their was minable lunar would be a good choice for charity.

“But we are paying several billion dollars a year for a space program and I do not think it’s unreasonable to require that we get something of value for that investment. ”

Generally, such a notion is wrong.

NASA goal should to lower the cost of doing anything in space.

What you are doing with mining lunar water, is getting rocket fuel to high earth orbit for about the same cost of

shipping rocket fuel to high earth orbit.

Getting lunar rocket fuel to high earth for same costs as shipping

rocket fuel from Earth, isn’t lowering rocket fuel at high earth orbit [in the near term], but it is achieving NASA goal.

Though it does significantly lower costs of rocket fuel at though lunar surface.

NASA job as ordered by Congress, is not get “value for an investment” this is something commercial companies must do.

It would a good deal or value if NASA only spend 40 billion dollar determining whether there was minable water on Moon. In same sense it would a good deal

if NASA only 200 billion dollars determining it was possible for something like the Shuttle to work.

NASA spend more than this and one say [be charitable] that results were “mixed”.

So one could say 40 billion dollar with a clear result is better than 200 billion with a mixed result.

And one say that if Chinese used technology from the Shuttle to successful

have a usable space vehicle, it would not be the worst thing to happen.

Likewise, if in future if NASA explored the Moon and found minable

lunar water, it wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen if some Chinese

billionaire successful commercially mined lunar water.

I would prefer an American or Japanese or European billionaire did this- but it’s waste of NASA investment to cause such thing sooner rather than decades or centuries later.

But what is desired is NASA to get more budget so it can do more space exploration, and I think a low cost and relatively quick exploration of the Moon

to determine whether there is minable water, is in to right direction.

This kind of “incremental” program is a recipe for failure. If it was was viable we would still be building the Panama canal. Likewise going after the social programs in the budget instead of the DOD programs with pieces made in every important congressional district make no sense either. While defense workers can become space workers, the same is not true of programs for feeding children and providing for the disabled. I have noticed scientists tend to get tunnel vision as much as anyone else and need a reality check just as often.

This kind of “incremental” program is a recipe for failure. If it was was viable we would still be building the Panama canal

Yeah, and we would still be building, extending and repairing interstate highways, railroads and port facilities — there’s a “recipe for failure” for you.

Now you’ve had your say. You reject this idea — we get it. Enough.

Could NASA and its traditional private vendors (Boeing, Lockheed-Martin, ATK, ULA,etc.) establish a permanent water and fuel producing lunar outpost with a $7 billion dollar a year manned space program within the next ten years? Of course they could.

But NASA has not returned humans to the lunar surface because of lack of funding. The Gemini/Apollo/Skylab program cost tax payers less than $140 billion in today’s dollars. NASA’s LEO programs (Space Shuttle & ISS) has cost the tax payers over $220 billion in today’s dollars since Apollo. That was plenty of money that could have been used to return to the Moon.

NASA hasn’t returned humans to the lunar surface because they have been politically banned from doing so. Lack of money is just used as an excuse by some politicians because they simply don’t want NASA to be anything else but a symbol of a pioneering space program.

Even George Bush’s lunar program prioritized replacing the Space Shuttle first with Ares I over immediately developing a heavy lift rocket and lunar shuttle to go to the Moon.

And, of course, President Obama bluntly banned NASA from returning humans to the Moon.

So NASA will return to the Moon once they are politically allowed to do so by Congress. I say Congress because despite the current President’s anti-Moon sentiment, he has really shown very little interest in NASA’s manned space program. Obama seems more interested in being buddies with billionaires like Elon rather than trying to help NASA’s manned space program!

Marcel F. Williams