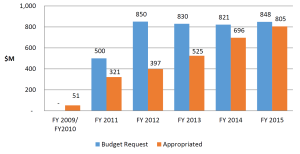

Budget requests (blue) and actual funding (orange) for NASA’s CCDev program. The “cuts” in the program are reflected in its steadily increasing budget with time. From Wikipedia.

The space media is in an uproar over the funding levels for NASA’s Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program. Congress has appropriated less money than the administration requested for the last five years. Has legislative parsimony held us back in our inexorable march to the stars? To read some of the press coverage, one might think so. But to gain some perspective, we should consider the origins and purpose of this program and what it has promised for what is being spent.

NASA programs to develop an independent, commercial capability to deliver both cargo and people to low Earth orbit have their origins in the strategic planning for the International Space Station (ISS) “assembly complete” era, and in the Vision for Space Exploration. One recommendation of the 2004 Aldridge Commission was for NASA to solicit cargo delivery to orbit from the commercial sector instead of launching it on government-built and -operated vehicles. The reasoning behind this recommendation was that as travel to and from LEO had become “routine,” and as NASA was supposed to be a cutting edge entity, it was time to contract for these services, so that the agency could focus its efforts on blazing new trails and technology paths. This recommendation (one of the few actually implemented from that report) became NASA’s Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) Program. The purpose of COTS was to invest seed money in the commercial development of this capability, after which delivery services for cargo to the ISS (the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) program) would be purchased.

The COTS effort began in 2006 and resulted in the development of two different American cargo delivery services, one by Orbital (Antares) and the other from SpaceX (Dragon); both are operational (although both are currently grounded by launch vehicle failures). On the basis of this apparent success, the current administration expanded the COTS concept into the realm of human spaceflight, called the Commercial Crew Development (CCDev) program. The ostensible purpose of this effort was to provide access to and from the ISS for American crew members by funding commercial companies to develop a new human spacecraft for LEO transportation. With the cancellation of Project Constellation, the need for crew transport to and from space was indeed pressing, especially as no attempt was made to delay the scheduled retirement of the Shuttle – it went forward unabated. Thus, our working orbiters were removed from service and put on display in museums around the country. We’ve been purchasing rides to ISS from Russia since 2011.

New Space adherents, believing that their ship had finally and truly come in, hailed the new emphasis on commercial spaceflight. In their formulation, “government programs” to develop new NASA spacecraft are ponderous, bureaucratic, slow and expensive, while the “private sector” of New Space would be nimble, responsive, fast and cheap. Much of the private sector’s incentive to be nimble and cheap flows from the reality that the expenditure of private capital impacts its shareholders, yet CCDev has the federal government paying development costs, a funding line that has been in NASA’s budget continuously since the program’s inception in 2010.

But when less money was allocated to CCDev than the administration’s yearly requests, its supporters grew incensed, intensifying the friction within an already divided space community. Much of their indignation stems from the concurrent full funding of the agency’s “program of record,” the new Orion spacecraft and its launch vehicle, the Space Launch System (SLS). In other words, because Congress chooses to expend more of the human spaceflight budget funding an established, federal human spaceflight program rather than transferring dollars to the new “private” commercial effort, they call Congress’ budgetary decisions corrupt and “pork.”

NASA claims that the selected CCDev proposals for spacecraft development are meeting their targeted incremental milestones. They further claim (through comments and letters to relevant Congressional authorities by the Administrator) that the “inadequate funding” of the program by Congress is responsible for the delays in system development and for extending the need for Americans to ride to the ISS on the Russian Soyuz. Is any of this true?

The Gemini program (1962-1966) created America’s first multi-person crew vehicle to orbit. The sum total of money spent on Gemini was about $1.3 billion (around $8.5 billion in FY2015 dollars) of which $800 million ($5.2 billion FY2015) went into the development and building of 12 flight spacecraft, and about 15 training vehicles, with the first manned launch occurring about 3 years after program initiation. The Gemini spacecraft carried two crewmen (although a later study considered development of a version that could carry up to 9 people). The spacecraft could maneuver to change its orbit and then rendezvous and dock with a target vehicle. Crew EVA was also supported and conducted on 5 of the 10 flown missions.

For the CCDev program (started in 2010), spacecraft designs were selected from three proposers for further development. Currently down-selected to two companies (Boeing and SpaceX), those contracts have met four development milestones in the past five years, but neither has produced a working spacecraft. To date, about $1.5 billion has been spent, with the two major contractors Boeing and SpaceX, getting $1.1 billion between them. Assuming that all certifications are met, manifests show the first unmanned demo missions of SpaceX’s Dragon is scheduled to launch in late 2016, and Boeing’s CST-100 in spring of 2017. The first crew delivery to ISS would be in 2017.

New Spacers claim this slow pace is the result of the Congressional under-funding, but offer no evidence that more money would significantly accelerate the schedule. Should we just marvel that the planners and builders in the 1960s got Gemini up and running in 3 years (at a point in which we had no experience whatsoever in space rendezvous and docking) and give this generation a pass? The “abundance” of money available to Gemini did not buy any schedule acceleration, although it did allow for the purchase of abundant surplus hardware. Like any spacecraft development, Gemini suffered several technical setbacks during its operational phase, including a wildly unreliable Agena target docking vehicle, early problems with fuel cell technology, and EVA difficulties that were not solved until the very last flight.

But a more pertinent issue is the whole concept behind CCDev. Allegedly, there is an enormous pent-up market demand for human transport to LEO and external “investment” or incentives are needed to kick-start, what will undoubtedly turn out to be, an economically self-sustaining industry. Yet several other attempts to do exactly this have failed to yield any positive results. Space entrepreneur Bob Bigelow set-up a prize in 2004 of $50 million for any entity that could demonstrate a capability for commercial human flight to LEO and return – that prize expired in 2010 without a single attempt to claim it. Why should the federal government pay commercial firms to build a vehicle that is desperately needed for private spaceflight? We’re told that NASA needs it for transport to the ISS. But we had working space vehicles – the Shuttle orbiters, whose retirement to museums was not halted after Constellation was arbitrarily cancelled.

The New Space paradigm isn’t faster and cheaper – although there might be some marginal differences, it’s just as slow and costly as any other approach to space. Spaceflight is hard (as the cliché goes) and attempting to accomplish feats on the very edge of technical possibility will always be difficult and costly. The “cuts” in CCDev imposed by the Congress are cuts only in the Washington sense – the actual amount of money appropriated for the program has increased each year. But there is no evidence that these “cuts” are responsible for the slow progress of the program. Commercial vendors of human spaceflight have only one customer at the moment (NASA), and as they are content to let the feds pay for their development, they are content with the current rate of progress. A test of the sincerity of their belief in the future commercial possibilities of human to LEO transport might be reflected in their willingness to back development efforts with their own money, rather than ours.

Excellent post Dr. Spudis!

Private enterprise only has a significant economic advantage over government enterprises— when there is a market substantial enough to accommodate the services of several competing companies. Competition is the fundamental great advantage of capitalism.

However, no substantial market exist for NASA’s commercial crew needs since they only require two to four crew flights per year to the space station. And even if Commercial Crew vehicles were part of NASA’s beyond LEO efforts, its doubtful that NASA would require more than one or two initial crewed flights per year to LEO. So, economically, there’s really only enough crew demand from NASA to marginally sustain the efforts of only one company.

However, the prices that private companies claim they will be charging for seats aboard their vessels ($25 to $40 million) would be affordable for at least 50,000 of the wealthiest people on Earth (those worth $100 million or more). If just 0.2% of that number (100 people) flew into space every year to a private commercial space station– that would require at least 20 commercial flights per year– a flight demand substantially larger than NASA’s needs. And that might be enough flight demand to sustain at least four or five different private companies.

The future of Commercial Crew development is not in a– big government space station program– its in private commercial space station programs.

Private commercial crew companies need to pool their money together to get one of Bigelow’s commercial space stations into orbit.

It might even be in NASA’s interest to commission an SLS cargo flight, before the end of the decade, to deploy Bigelow’s largest private space habitat into orbit (the BA-2100) in order to help create a vibrant Commercial Crew industry for both private customers and for NASA’s needs in the next decade.

Marcel

Hi Marcel,

“If just 0.2% of that number (100 people) flew into space every year to a private commercial space station– that would require at least 20 commercial flights per year– a flight demand substantially larger than NASA’s needs. ”

I understand the thought (a market for 20 launches/year for 500 years) but that assumes that all 50,000 would want to fly at all and would then wait there turn in the 500 year long line (have a feeling those at the 10 year point would lose a lot of enthusiasm).

This would be based (as I understand it) on tourism. A lot of that would be based on doing it being considered “special” – thus stroking the egos of the hypothetical tourist. That may work for the first 100 people (the first year of the tourist trade), but what about the second 100, third 100, etc. For those kind of folks novelty tends to be a very perishable commodity.

I do not believe there will be a viable commercial market to LEO unless/until Cis-Lunar Space is developed to the point of requiring a sufficient number of people to do actual work in space to generate it.

When/if that happens a space tourist trade could “piggy back” on it.

Thanks for your comments Joe.

I believe that at least one out of three people on Earth would love to travel into space. A recent Monmouth University Poll, however, suggest that only 28% of Americans would travel into space if they had a free ticket. But that poll was taken right after the Virgin Galactic crash.

So there are probably billions of people on Earth who would love to travel into space. That’s one of the reasons that I frequently advocate a Space Lotto system to promote space tourism.

Amongst the supper wealthy, however, I suspect that only about one out of ten people would actually be willing to pay big money in order to do so– if they could afford it and they knew it was pretty safe– and there was an interesting destination (a large commercial space station).

So that would be about 5000 customers. If you assumed that only 10% of that number would get around to traveling into space within a 10 year period, that would average out to be about 500 customers per year, 100 flights per year.

So I thought I was actually being ultra-conservative in my 10 flights per year scenario.

New generations of super wealthy customers would of course emerge to replace earlier customers as the decades rolled on.

That amount of demand, of course, would probably dramatically lower the cost of space travel which would substantially increase the number of people wanting to travel into space.

But there’s no doubt in my mind that if private tourist oriented space stations are deployed and the launch vehicles are safe, the demand for space travel from the super wealthy and space lotto winners will be very high.

Billions of dollars are already made annually from people virtually traveling into space through television and movie scifi films and video games.

Marcel

“The future of Commercial Crew development is not in a– big government space station program– its in private commercial space station programs.”

If that were true then there would already be dozens of “vibrant” private space habitats making money hand over fist.

It is not true, it is not going to be true, and the entire NewSpace fantasy will end in bankruptcy and ruin. There is no cheap and there will be no cheap.

It is not that “space is hard”; it is that you get what you pay for. LEO is a dead end. Mars is a dead end. Telecommunications, defense, and energy are what make money. Telecom is in GEO not LEO. The space stations, spaceships, and resources to create a space solar energy industry can come from only one place- the vastly shallower gravity well of the Moon.

NewSpace is flim flam, a scam, a confidence game. Only vast governmental resources can build a cislunar infrastructure to enable industry in space. NewSpace is preventing that public works project from happening and is the worst thing that has ever happened to space exploration.

You can’t have a private space station program without a private Commercial Crew program. A private space ships– routinely– carrying NASA astronauts and tourist into orbit probably won’t happen until the end of this decade.

Marcel

The ISS is deteriorating. The money required to keep it operating goes up every year and this will turn exponential by “the end of this decade.” Before that happens someone is going to throw the B.S. flag and that will be one more nail in the NewSpace coffin. While China may have a few cans going in circles to test equipment the ISS is the last long duration LEO space station.

Nobody is going to invest a dime in a private space station because there is no way they will ever see a return.

At some point the entire wonderful fantasy that 200 miles up is outer space will begin to unravel and the voters will find out it is a scam. Hopefully the next administration will change direction and defuse this ticking bomb before it does permanent damage to the space agency.

Paul –

There are several inaccuracies, false statements, and incorrect conclusions in your post that need correcting; and I’m afraid they require an extended response. Sorry.

1. Referring to Commercial Crew as “CCDev”: The Commercial Crew Program has been in 4 distinct parts (5, if you count the Certification Products contracts): CCDev1, CCDev2, CCiCap, and CCtCap. It’s not just a nomenclature difference; CCDev1, 2, and CCiCap were all done under non-contract Space Act Agreements like COTS cargo, where, among other things, the companies were supposed to put their own monies (ie, “skin in the game”) (all but one did). The Certification Products contracts, and the current CCtCap contracts, are not Space Act Agreements; rather, they are FAR, fixed-price contracts.

2. That the US government should help stand-up a commercial cargo resupply industry for LEO came before the 2004 Aldridge Commission. Following testimony in the ’90s before Congress by the Space Frontier Foundation (I believe it was Rick Tumlinson) that resupply of the ISS in the future should be done by commercial industry as the beginnings of a LEO commercial infrastructure, Congress passed the Commercial Space Act of 1998, which among other things states that NASA is to get serious about turning LEO over to the private sector, starting with services to the ISS, and mandated NASA provide several studies to Congress detailing how that was to happen. (I’ve appended excerpts from the Act at the end of this; I won’t take up space here).

3. The national goal of both COTS/commercial cargo, and later commercial crew programs, went beyond ISS: the extensibility of each to non-ISS, non-government customers (e.g. private space stations, such as a Bigelow modules), were explicit reasons for both programs, including how they were evaluated for their Space Act Agreement awards. (That is less true for this final phase develop of CCtCap, where NASA lawyers insisted that to put requirements related to the transport of government employees– ie, NASA astronauts — to the government-owned ISS, required FAR contracts that were ISS-specific).

4. Your implication that there is basically only one way to develop spacecraft – the government way – is simply incorrect. I’ve worked in both the Space Shuttle Program Office and the Space Station Program Office in my 40-year NASA career; you can not get a more inefficient, time-extending, cost-inflating, way of business than the way we often (usually) have to do things. That’s why internal, NASA-designed, owned,, operated, etc. programs must be reserved for things the private sector simply can’t, or won’t, do, under any circumstances; including the cutting-edge, first of a kind stuff, things that won’t be ‘economic’ for a long time, etc.

5. For things that fall in the middle – ie, the things that are not yet fully commercial, but could be with the right investment from the government – the COTS program has indeed shown us a better way. (And I do consider COTS/CRS a success. In fact, SpaceX, for one, with one failure in the first 19 flights, is demonstrating a much better launch record than the Ariane V did, which at the same point in its lifetime had two total failures and two partial failures. It’s gone on to have, what, almost 70 straight successes since? Though at a much higher equivalent cost than SpaceX; and, unlike SpaceX, you don’t even get anything returned to Earth afterwards).

6. Your implication that there is no cost savings where a COTS-like, public-private partnership development is appropriate, is simply wrong.

– The first example where we have data is the private development of SpaceHab for use on the space shuttle (and later at ISS). In fact, Congress mandated a separate audit the SpaceHab effort to see if it was cheaper than NASA could have done itself. The independent auditor found that, at approx. $150m development cost – privately paid – Spacehab likely would have cost NASA 8 times more if we had done the module the usual NASA way. (Price Waterhouse SpaceHab report, 1991, “Analysis of NASA Lease vs Purchase”).

– The second example is the USAF EELV launcher program, which yielded two separate, competing launchers at much less reduced cost to the government because both Lockheed and Boeing were, like in COTS, in charge of development and put their own money in, with the USAF providing funds more as an investor would. Both rockets – including a new engine in the case of the RS-68, were developed more quickly and at less expense to the government than if it had been done the government -owned, designed, controlled, and operated way. (What happened with the EELV program years later, as commercial markets collapsed and the ULA monopoly was encouraged/allowed to form, is a totally separate story from the actual development of the new rockets and engine to begin with). (Within DOD such agreements were called OTA, Other Transactional Authority, not Space Act Agreements).

– then came COTS, which as in the early EELV days, was a public-private partnership, where the government partner – in this case NASA – was no longer ‘in control’; used Space Act Agreements to set specific milestones to be met in exchange for investment (but not oversight and control), and which very deliberately made sure there was more than one competitor so that a single company couldn’t hold us by the cajones. COTS was a great success; and was was reported after the program, over 50% of the total investment done in each case, Orbital and SpaceX, was made by the companies themselves; with the NASA investment closer to 45% in each case. And the two sets of systems were done much quicker than a government-controlled program would have been done in (one of the ways costs were controlled. Since the companies were paying over 50% of the cost, they were automatically incentivized to control the costs and schedule. As opposed to that, our usual cost-plus contracts in the NASA manned space business, actively disincentivizes contractors from controlling costs and schedule, in many ways).

NASA did its own study comparing SpaceX’s actual Falcon 9 development costs, with what it would have cost NASA to do it business as usual; the difference is not a few tens of percent, but several hundred percent.

(http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/586023main_8-3-11_NAFCOM.pdf)

– Public-private partnership development can even be done on the component level, by the way. An example that’s flying now: the Sabatier water generator on board the ISS. It was developed, delivered, and is in operation; privately developed by Hamilton Sundstrand, with some – but not all – of the development money provided by NASA. NASA also had a 100% clawback provision for its funds in case we got it up to ISS and it didn’t work. Now, Ham Sundstrand is paid based on the unit’s ability to successfully generate water without a problem; showing that the public-private partnership model can save government money, and schedule, even when done on the flight component level.

7. Lastly, the subject of ‘skin in the game’: One major difference I’ve seen in Commercial Crew vs Commercial Cargo: the initial Commercial Crew Space Act agreement awards, like those for COTS/commercial cargo, were evaluated not just on technical matters, but on financing, and the amount each company had “skin in the game” by providing funds from their side. Only one Commercial Crew company apparently refused to provide funds for their share of Commercial Crew development; and that was/is Boeing. I was not the only one surprised, when Boeing was awarded two awards in spite of the fact that they were not putting “significant” (according to Gerst’s Selection Statement) (usually take to mean “zero”) internal funds into the program. Not only have they gotten the awards; they’ve received the largest amount of the awards, in spite of refusing to put any skin into the game themselves. In my personal view, to give by far the largest awards to the one entity that put the least (to put it mildly) into the program, sends exactly the wrong signal, and in fact possibly, again in my view, encouraged Boeing’s insistence on such a large contract amount in CCtCap, after they were awarded a large amount in CCiCap in spite of not investing much. Why NASA chose to ignore it’s own evaluation criteria when it came down to one particular company has, in my personal opinion, never been fully explained.

So, the bottom line:

– Public-private partnerships – where appropriate — can provide very real space capabilities, including launch vehicles and spacecraft, at a fraction of the cost of a government-run space project, and in much shorter time, if done correctly. In the case of SpaceHab, EELV development, and COTS commercial cargo, they were real successes we can and should consider using for the future.

– While the jury is still out on Commercial Crew, it’s development path has been slightly different from cargo, and is a mix of private-public partnerships and traditional government contracting. But there seems to be no question than that it is costing the government less money to do this mixed model – and get two competitors out of it – than if we in government were to go it alone in our traditional, very expensive way.

– To imply you can cut huge amounts out of the government’s part of the development budget of these commercial human spacecraft, without having a schedule slippage, is simply……..what’s the word I’m searching for??…….wrong; and it’s such an illogical suggestion on the face of it it’s not even worth ‘debating’.

– It is factually wrong to state that Congress took money from Commercial Crew (and, just as bad, decimated the Space Technology account), to “fully fund” SLS and Orion. SLS and Orion were already fully funded, as NASA officially testified several times to Congress. Congress negatively impacted commercial crew and space technology solely to further plus-up funding in certain states; requiring NASA in the case of crew to spend yet another half-billion dollars on Soyuz; all without accelerating the launch date for SLS/Orion by a single day!! The congressional actions were wrong for America on all levels, and are indefensible.

– the COTS model can, almost certainly, be extended to support segments of cislunar and lunar development. That is the single most important conclusion of the Charles Miller-led Evolved Lunar Architecture study, and I agree with it. We can get more lunar-related development done, faster, for less money, and with more extensibility and permanence – i.e., more “legs” – by selectively using the public-private partnership model where it is appropriate.

Dave Huntsman

My opinion only.

– Excerpts from the Commercial Space Act of 1998:

(a) Policy.–The Congress declares that a priority goal of constructing the International Space Station is the economic development of Earth orbital space. The Congress further declares that free and competitive markets create the most efficient conditions for promoting economic development, and should therefore govern the economic development of Earth orbital space. The Congress further declares that the use of free market principles in operating, servicing, allocating the use of, and adding capabilities to the Space Station, and the resulting fullest possible engagement of commercial providers and participation of commercial users, will reduce Space Station operational costs for all partners and the Federal Government’s share of the United States burden to fund operations.

………….The Administrator shall deliver to the Committee on Science of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation of the Senate, within 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, an independently conducted market study that examines and evaluates potential industry interest in providing commercial goods and services for the operation, servicing, and augmentation of the International Space Station…………

………the Federal Government shall acquire space transportation services from United States commercial providers whenever such services are required in the course of its activities. To the maximum extent practicable, the Federal Government shall plan missions to accommodate the space transportation services capabilities of United States commercial providers…………..(a) Policy and Preparation.–The Administrator shall prepare for an orderly transition from the Federal operation, or Federal management of contracted operation, of space transportation systems to the Federal purchase of commercial space transportation services for all nonemergency space transportation requirements for transportation to and from Earth orbit, including human, cargo, and mixed payloads. In those preparations, the Administrator shall take into account the need for short-term economies, as well as the goal of restoring the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s research focus and its mandate to promote the fullest possible commercial use of space.

Dave,

In future, very long comments like this one will not be approved — post this on your own blog.

You have very selectively quoted my post to prove your preferred opinions. I do not care that you are big fan of the current direction. I simply interpret things differently than you do.

I do not say that the “government way” is the only way. I am saying that the current so-called “commercial” path is neither commercial nor has it been a totally successful path. We currently have much less capability in our civil space program yet spend essentially the same amount of money for it. You have no evidence that more money thrown at CCDev would advance the first launch any sooner than now planned. I do not care what some politically loaded NASA report concluded that the agency’s current commercial endeavors were great bargains and models of enlightened policy — with this lot running things, do you think that anyone would ever see a negative report?

But beyond the specifics of this program, I have a bigger issue — if these new capabilities are to be considered “private”, then the companies that are making them should foot the bill for their development. “Commercial space” in this day and age is simply crony capitalism, comparable to subsidized “green” energy and the Ex-Im bank.

Mr. Huntsman,

Per Dr. Spudis’s response above I will refrain from responding to your attempted book piece by piece.

However, I will make reference to one of your many questionable assertions:

“It is factually wrong to state that Congress took money from Commercial Crew (and, just as bad, decimated the Space Technology account), to “fully fund” SLS and Orion. SLS and Orion were already fully funded, as NASA officially testified several times to Congress. Congress negatively impacted commercial crew and space technology solely to further plus-up funding in certain states; requiring NASA in the case of crew to spend yet another half-billion dollars on Soyuz; all without accelerating the launch date for SLS/Orion by a single day!! The congressional actions were wrong for America on all levels, and are indefensible.”

It is that assertion that is factually wrong.

Every year the Administration “fully funds” the “Commercial” Crew program at the expense of SLS/Orion per the SLS/Orion budget levels agreed to in Public Law 111–267 (42 U.S.C. 18323) as passed by Congress and signed by the President – not whatever arbitrary level the Administration decides unilaterally from year to year.

Every year the Congress (on a bi-partisan basis) puts the money back in SLS/Orion leading to the “under funding” of “Commercial” Crew. This restoration of funds is to bring the funding for SLS/Orion into line with the Public Law noted above, which is supposed to be the governing law – actually following the law (as signed by the current President), what a concept!

This kabuki dance takes place every year in spite of the fact that the amount of money in question is about 0.01% of the yearly Federal Budget.

If the Administration actually cared whether or not “Commercial” Crew is “fully funded” they could come up with the extra money. The obvious real objective is to try and cut SLS/Orion funding below the previously agreed to levels in order to damage the programs as much as possible

Additionally it sets up a false argument of SLS/Orion vs. “Commercial” to divide any politically active space advocates.

Sadly this kind of political chicanery is working all too well.

In 2002 the NewSpace flagship company came into being and a legion of Ayn-Rand-in-space NASA-hating libertarian Space Clown wannabe’s have since fanatically marketed their scam. This infomercial has so contaminated any public discourse it is impossible to find anyone casually interested in space flight not exposed to misdirection and deception. In the tiny internet subculture of Human Space Fight advocates this gang of cyberbullies and their gutter tactics have almost completely silenced any attempt to expose the lies. Almost.

Since the hobby rocket blew up the NewSpace mob is having trouble keeping the facade presentable. The best any true space advocate can hope for is a change of direction with the coming change of administration. The two faced double agents placed in the NASA hierarchy will be shown the door and the useless space station to nowhere and taxi programs ended. And Mars will be seen for what it is; a P.R. hook, a gimmick, and a farce.

The Moon is waiting.

As columnist Eric Berger writes in an article Dr. Spudis provides a link for:

“Let me be very candid,” Bolden told me last year. “I am not baffled by opposition to anything that the President puts forward. Very blunt. Republicans don’t like the President. They have stated very clearly that will oppose anything he puts forward, that they will not allow anything to go forward that gives him credit for anything, and I think that’s very unfortunate. But that’s politics.”

As a Democrat and a space advocate this really sickens me. It really is “politics” from a NASA administrator that obviously has two bosses- one in the White House and one in Hawthorne. That the tooling and workforce at Michoud is only capable of producing a few Space Launch System cores a year and one of two launch pads has been given away to SpaceX tells the real story.

While Bolden wails and gnashes his teeth over NewSpace not getting all the corporate welfare it can suck up the only Super Heavy Launch Vehicle on Earth and the only one designed to take astronauts Beyond Earth Orbit is neglected and not to be discussed. Disgusting.

“Why should the federal government pay commercial firms to build a vehicle that is desperately needed for private spaceflight?”

The answer to that question is found in a campaign contribution and subsequent “been there” speech. Going to the Moon with a SHLV bypasses LEO and dumps the NewSpace business plan in the trashcan. When this kind of arrangement is played out for years with nobody admitting to what is obviously going on it usually ends with people in handcuffs doing the perp walk.

Of course nobody ever went to prison for designing a launch vehicle with no escape system that eventually killed two crews. Stranding the U.S. space program in LEO for several decades and directing billions of tax dollars into creating a private space company launching commercial satellites for profit might be overlooked also.

I am not certain why anyone would think that all systems development costs about the same and that “newspace” does not provide capabilities at more reasonable prices than the legacy companies like Boeing and Lockheed.

I have worked as a systems engineer and developer on Shuttle, ISS, and Spacehab, and on the integration and certification of systems and payloads on Apollo, Shuttle, Spacehab, Spacelab, Mir, Soyuz, Progress and ISS.

NASA processes are difficult. They are difficult because of the complexity and overlapping responsibilities of NASA centers and even the organizations within individual NASA centers. And they are difficult because in many cases there are conflicting documentation requirements and processes.

Dave Huntsman points out, correctly, that the development cost of Spacehab was many times cheaper than development of any similar NASA system. I can tell you, it wasn’t just on paper; it was real.

It is not because NASA could not improve and expedite processes; it is because the turf battles between directorates and centers have never been resolved. Within the ISS program they have a dozen divisions, many of which overlap in their functions. The conflicts are never resolved because people without the appropriate experience are put in charge and they really have no idea of what is required or how they should go about resolving turf issues.

When we needed to launch hardware to Mir, the Russians could handle expediting hardware with a couple of days to integrate-the longest pole was often the logistics of getting hardware to the remote launch site. Spacehab, which was the primary logistics carrier on Shuttle for the Mir missions, could handle new hardware a couple days before launch, but to integrate through the Shuttle system took 2-3 months. Even if it was hardware similar or identical to what was already in orbit, the Shuttle program wanted to do stowage drawings and run through their multiple stage safety review process while Spacehab and RSC Energia could assign a technical specialist, review the hardware and documentation and provide an approval. ISS is by far the worst of the systems. They have so many organizations all claiming responsibility for similar functions that it is difficult even to find the entry point for hardware development, certification, or for payload integration.

And the Shuttle or ISS program offices were only the “front” for the operations organization which had responsibility for most activity in orbit, so even if you got through the program offices, you still might be faced with problems with Mission and Crew (astronaut) operations.

Nanoracks and Cubesats have gained notoriety on ISS because they take only 6-9 months to fly. But they are essentially self-contained and require minimal crew interaction, and so can bypass most vestiges of the ISS integration organization. But they are barely passable as man-tended; certainly not man-operated.

The Space-X Dragon capsule which has flown successfully 8 times, is a block I of the Dragon manned system. It has tested out most of the required systems. Its been flying 5 years and was in development only about 4 years. It has cost the US taxpayer in the low hundreds of millions of dollars. Development started shortly after NASA started development of the Orion capsule.

Orion, by my calculation, is now up at around $15 billion and by the way that is money spent only for the Orion command module as ESA is developing a service module based on the ISS ATV in trade for resources NASA provides on ISS, so total cost to NASA has been higher but hidden in ISS costs. Orion has not flown. What flew last year was at best a stripped down boilerplate.Orion will not fly for many more years and many more billions of dollars. Despite the NASA hype about Orion being the first step to Mars, it doesn’t have much capability beyond the Space-X manned Dragon. Its about the same size, the current version has similar capacity, it has a little larger Delta-V, but carries a smaller crew complement.

The 100s of millions of dollars per year reflected in the table you provide, shows very clearly that NASA is getting a lot for relatively little money. NASA-which represents the Administration, has made promises which the Congress has not supported. If it had been a different deal, then maybe the work would have proceeded more quickly. The Gerstenmaier decision to support Boeing, which provides yet another redundant capability to Dragon and Orion and at full cost to the government, was unfortunate but note it is still costing a lot less than the NASA managed Lockheed built Orion.

Rich,

You are very eloquent in presenting your viewpoint, but like Dave Huntsman, you have ignored the main points of my post.

I am not arguing against Boeing or SpaceX developing spacecraft — I am saying that commercial vehicles should be developed commercially. I have no problem with any company coming to NASA, offering a working spacecraft system for crew transport to ISS, and then being paid appropriately for that service. What we have instead is another federal crony capitalist program for companies to develop spacecraft and capability with taxpayer money, after which taxpayers will then obtain the privilege of purchasing their services at significant additional cost. I don’t care how you cut it, that is not “commercial” space activity — it’s government contracting. If the (continually increasing) amounts of money provided to CCDev companies for spacecraft development are inadequate, those companies should make up the difference with their own internal R&D funds, provided to them by their shareholders.

I have no disagreement with you that federal programs are an inefficient and expensive way to do things – but they are a way to get things done (or at least, they used to be). I fully concur that multiple layers of management in NASA projects have been counter-productive and have ranted at length on these issues. But today’s agency has problems much deeper than managerial sclerosis — it is directionless and clueless. That problem dwarfs the issue of how we contract for new space hardware.

Comparing development issues for Orion and CCDev is apples and oranges. Yes, the promotion of Orion as a “Mars spacecraft” is overdone hype, but cislunar is a notch above LEO and poses correspondingly different technical issues.

The 100s of millions of dollars per year reflected in the table you provide, shows very clearly that NASA is getting a lot for relatively little money

So far, they have spent over $1.5 billion and have gotten zilch in return. Unless you count the New Space propaganda as “a lot.”

“As the years wore on, it began to dawn on some of us that some within and outside the agency really didn’t want to go anywhere or do anything in space. Working for NASA means being involved in the process of working.”

One of my most enlightening experiences in the military was when the Coast Guard “adopted” Total Quality Management in the 90’s. I spend an hour or so a day reading and always have since I was a kid. I read all kinds of stuff. I knew we were having mandatory training on TQM coming up so while at the library I checked out a stack of books on it. When I research a new subject I usually start that way- and set most of the books aside after scanning them to see if they are worth studying. I quickly realized why somebody in the hierarchy decided on TQM. It works. I won’t go into arguing this except to say if you go into the lobby of Toyota’s headquarters in Tokyo you will see 3 portraits on the wall; two small ones of the companies first and present CEO’s and in the center a much larger picture. That portrait is of W. Edwards Deming- the father of TQM. The highest award for engineering in Japan is the Deming award.

I was excited but when the training started it quickly dawned on me that what the Coast Guard had adopted was not TQM- it was someones or more likely some committee’s morphed and mutated idea of what TQM should be. I pointed this out in class repeatedly as violations of Deming’s 14 points were presented and was finally ordered to remain silent- and was counseled later about my disruptive behavior.

I would add the “red bead experiment” is a fascinating example of what “process” is about. During WW2 Deming worked on improving the quality of munitions and it should be noted that U.S. explosive devices were not in the habit of blowing up in soldier’s faces while most everything else made did. Including rockets. I accept Deming’s conclusion that 94 percent of problems in production can be traced to management because of another WW2 example. The entire first year of our war in the Pacific our submarines had defective torpedoes. U.S. submarines eventually sank over half of the Japanese merchant fleet while representing 1.6 percent of the U.S. naval effort. Since few merchants ships were left after 44 this part of the war only lasted about 2 years and for half of that “management” was attributing torpedo failures to “poor maintenance” by the submarine sailors. There are many other examples.

The point being the story that NASA and “old space” companies are horrifically wasteful and inept while “NewSpace” is doing it right and also miraculously cheap is not reality. It is marketing. The hobby rocket blew up and ULA rockets have not and the story the public seems to accept is not what is real.

There is no cheap.

Rich,

Very few people who have worked within the NASA System would disagree with you that it has become an overly complicated bureaucracy. That situation began to develop at the end of the Apollo Program (when the NASA budget was cut in half, but the field centers all stayed open; setting the stage for the development of the current “warring empires”) and is long overdue for reform.

That, however, is not the question. The question is about the efficiency of the current “commercial” approach.

SpaceX CRS contract calls for the delivery of 20 Metric Tons Cargo to the ISS for $1.6 B. That is $80,000/kg.

I worked in shuttle cargo integration for a while and there were detailed analysis of the costs of MPLM payload delivery (even taking out the mass of any packing material) on a standard utilization flight. The figure was around $70,000/kg.

SpaceX CRS is, therefore, 14% more expensive than Shuttle to operate.

Using the “commercial” approach we spent years and $100’s of millions of dollars to develop a cargo delivery system that is substantially more expensive to use than the one it replaced.

You say:

“I am not certain why anyone would think that all systems development costs about the same and that “newspace” does not provide capabilities at more reasonable prices than the legacy companies like Boeing and Lockheed.”

The above explains why “anyone” would doubt that “newspace” is an overall bargain.

The development of the Orion vehicle may be one of the biggest boondoggles in the history of space travel. And I seriously doubt that it will ever have anything to do with human missions to Mars in the 2030s.

The SLS, on the other hand, may be one of the best bargains America’s space program ever developed!

I seriously doubt there will be any “human missions to Mars in the 2030’s.” There is no reason to go there and the only way to get out there (build a true spaceship) will require a large Moon base to jump off from.

As for the Orion being a boondoggle, there are a half a dozen or more DOD projects that make Orion look like chump change. I would cite a few that really do make Orion look incredibly cost effective in comparison but Dr. Spudis does not like me going in that direction on his blog.

Orion is meant for cislunar space missions and features a very powerful Launch Abort System. This is important because any missions Beyond Earth and Lunar Orbit (BELO) will require nuclear propulsion.

Chemical propulsion is useless for any human interplanetary missions.

The SLS/Orion-LAS is the best way to transport fissionable material directly to the Moon. If you think the toxic dragon is going anywhere…. it has so many bad design features I will not even attempt to start listing them. I doubt it will ever carry a human being.

One thing about the Gemini program that was smart was that it took an existing rocket, in this case the Titan ICBM, and rated it for manned spaceflight. I imagine such a move, plus the other adaptations of existing ICBMs for human flight, definitely saved time and money.

Boeing with its CST-100 seems to be doing things right, as they intended Atlas V to be human rated. Of course, who knows if that will happen?

I see SpaceX’s big problem (and I know people here will point out many) is that they’re trying to make a human rated rocket AND a spacecraft.

Even worse is how much time and money they must be pouring into making Falcon 9 reusable rather than getting their spacecraft ready to carry humans. Not smart, IMHO.

I’m often amazed on how many people have this mentality of just how much better “commercial” spaceflight is compared to “government funded” counterparts.

I imagine many here have seen the hype. I’ve even seen one person that ought to know better (but I imagine has fallen too deep into the hype) that it would be better to spend the money used on SLS and Orion on CCDev.

Perhaps if NASA had actual plans for meaningful missions for the SLS, people wouldn’t feel so opposed to just. But that’s merely speculation.

“I see SpaceX’s big problem (and I know people here will point out many) is that they’re trying to make a human rated rocket AND a spacecraft.”

Not really. Trying to go cheap is their problem. In my view the defining moment of the Apollo program was the Apollo 1 fire. After that event everything about the space program changed- it was a sea change, a paradigm shift- whatever term you like. It taught the aerospace industry that Human Space Flight was going to be hard money and they were not going to get rich as long as NASA required spacecraft that did not kill astronauts before they ever left the ground. The draconian oversights imposed were eventually removed for a Shuttle program seeking “cheap and routine” and fatalities were squared.

North American also built the second stage of the Saturn V which is credited by Mr. Brown as being the key enabler of Apollo’s success. The epic story of developing that second stage is a little known yet essential explanation of why we landed on the Moon.

There is no cheap.

Taking a look at these historical details it appears that basing an entire business plan on “cheap lift” and then having a second stage blow up in flight will probably be viewed as the defining moment in the short history of NewSpace. The space age ended in 1972 and as long as the public is hoodwinked into believing “the dream is alive” the U.S. will stay trapped, going in endless circles at very high altitude, going nowhere.

LEO is not even really space.